What I'm Reading About the History of Venture Capital and Game Development

Plus some quick book, game, and TV recommendations

This week I’m sharing some books, a game, and a TV show I’ve been enjoying. I want to talk particularly about one book that changed my understanding of the historical relationship between the games industry and venture capital.

It’s been just a few months since I took a job working at a16z, and ever since then I’ve been trying to figure out how the hell this “venture capital” thing works.

Until recently I didn’t know jack squat about VC—though I’ve worked for venture-backed companies (Riot, EA, Odyssey) for most of my career. It had never occurred to me to look into the history of the space or the stories behind its major players. And I definitely couldn’t tell you how a term sheet worked.

So I decided to hit the books. Physical books, audiobooks, podcasts—I’ve just been trying to learn everything I can.

For a nitty gritty understanding of the way modern VC works, Scott Kupor’s Secrets of Sand Hill Road (2019) is excellent, and goes into great detail about how the terms and incentives in VC deals are organized. It’s almost literally required reading for anyone thinking about working in VC. The Andreessen Horowitz team sends you a copy in a box as part of your onboarding package (Kupor was employee #3 at the firm after the co-founders, Marc and Ben).

But an easier point of entry is Sebastian Mallaby’s The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future (2022). Mallaby’s credentials are as good as it gets when it comes to financial and economics journalism: He’s a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist who has written definitive books about the hedge fund industry, plus a biography of Alan Greenspan. He was also a longtime editor for The Economist, all of which is to say: dude knows how to write about dollars and cents.

But The Power Law isn’t some dry economist’s take on VC. It’s written as a work of popular history and focuses on the most dramatic and extreme stories from the history of VC. Mallaby tells how a Cisco cofounder did a nude photoshoot on a horse, how much pot the Atari guys smoked, and how Masayoshi Son pulled gangster moves to force the founders of Yahoo! to work with him.

Here’s how Mallaby introduces two major players in his story:

The chief pioneers of the new venture style were Don Valentine and Tom Perkins, the prime movers, respectively, of the great Silicon Valley rivals Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. They were equally forceful and equally suited by temperament to combative activism. Valentine is said to have remarked that underperforming company founders should be “put into a cell with Charlie Manson,” and he once berated a subordinate so severely that the poor man passed out. Perkins, a Ferrari-driving, yacht-owning, self-regarding dandy, loved to flout polite wisdom; in later life, when he splashed $18 million on an apartment in San Francisco, he declared defiantly, “I’m called the king of Silicon Valley. Why can’t I have a penthouse?”

—Sebastian Mallaby, The Power Law, page 60

That’s good stuff. Of course, the book isn’t only about the zany side of VC—it also lays out a pretty compelling case for rethinking the history of Silicon Valley, the computer industry, and the history of the internet. And Mallaby ties the tale neatly around the key theme of venture capital, which really is all built around the idea of power law distributions.

Put in plain speak, you can understand the VC business this way.

Venture capitalists invest capital from LPs (limited partners) into early stage companies in exchange for equity (partial ownership of the companies). Many of these companies are wild bets, where success is far from guaranteed. It is expected that many (most?) early stage VC investments will fail outright.

This sounds like a terrible business model, because VCs can’t expect to recoup most losses. Founders that lose money generally aren’t expected to pay it back.

However, the math works out because some successful early stage investments can pop off to an extraordinary degree. If you find one company that returns 500x your investment, you can afford to strike out on many others.

Mallaby’s book is in part a catalogue of those rare VC-backed companies that delivered massive returns, like eBay, which returned 750x in only two years for VCs Benchmark Capital. There’s a parade of these insane stories in The Power Law, and it’s worth reading for the entertainment factor alone, but I think the real value of the book is the broader historical picture that it paints.

Two specific historical ideas from the book jumped out at me:

Though the history of Silicon Valley is usually told from the viewpoint of heroic founders, there’s a parallel history of the valley that’s also the history of modern venture capital itself. The two have been tied together since the day in 1957 that Arthur Rock (who coined the term “venture capitalist”) convinced the traitorous eight to leave their jobs at Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory and form Fairchild Semiconductor.

The Western games industry was nurtured by the same venture capital network that funded the nascent computer industry and the commercial internet. The first investment ever made by Sequoia Capital was in Atari, in 1975. The same guy who funded Atari—Sequoia founder Don Valentine—introduced the founders of Apple to their first investor.

I don’t want to overstate the role of VC in games. Certainly there are countless important games studios and companies that were bootstrapped or funded by publishers. But many legendary games studios were VC-backed at one point or another: Epic Games, Zynga, King, thatgamecompany, Roblox—the list goes on. And many people that work at these companies today are probably unsure how VC works or the role VCs play.

If you look into the historical connections between VC and the games industry, the image that emerges is of a tangled, organic ecosystem. Capital funded the companies at the heart of Silicon Valley, and games in turn drove consumer demand for the products created by the valley’s giants. As the computer world bloomed, games emerged as the dominant computer-native art form. And the nature of venture capital itself evolved alongside both.1

I reached out to The Power Law author Sebastian Mallaby via email to ask him for his view on the relationship between VC and games, and he agreed that the connection goes deep: “Games drive demand for smartphones, screens, developer tools, and so forth, and this helps the tech industry,” Mallaby wrote. “At the same time, some games companies have raised venture capital, although there have been other models.”

Sidebar: From God Game to Protein Discovery

Mallaby, who is currently researching his next book, shared an anecdote I’ve never heard before: “When Demis Hassabis of DeepMind founded a game studio named Elixir, he tried to raise venture capital in London but in the end had more success striking a deal with a games publisher,” Mallaby told me.

Hassabis got deserved attention last year when he won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on protein structure prediction using AlphaFold 2. Less well known (to me at least) was his origin story as a developer working for Peter Molyneux at Bullfrog Productions in the 90s. Hassabis later followed Molyneux to Lionhead, where he was credited as the lead AI programmer on the legendary “god game” Black & White.

There’s much to be written about the long, twisting connection between games and venture capital. But perhaps there’s even more to be said about the long incubation of artificial intelligence within the games industry.

The history of the games industry has only just begun to be written. Books like The Power Law show how many vital threads connect even the earliest games to places (Silicon Valley) and forces (VC) that are still shaping the world.

One more historical adventure book I’m enjoying

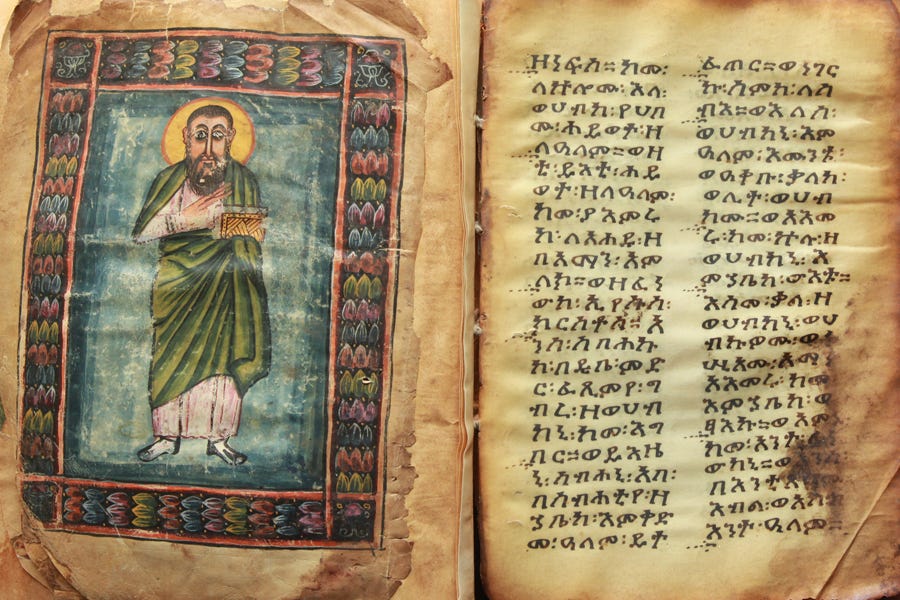

I’ve written here before about my obsession with religious history (Christian, Islamic, Mormon, Hindu—whatever), and last month I really enjoyed The Bible: A Global History by Bruce Gordon. It basically tries to explain how the major translations and editions of the Bible came to be, and in doing so tells a fascinating story about the evolution of language itself. It also tracks a ton of wild subplots, like the one about the ancient order of Ethiopian monks that have been successfully guarding the world’s oldest complete illustrated Christian manuscript for 1,500 years. I listened to this one as an audiobook and highly recommend it.

A gorgeous RPG set in the high middle ages

Kingdom Come: Deliverance II has sparked a bunch of braindead culture war debates online, which is frustrating because the game deserves more serious consideration. I’m not usually such a sucker for these super deep open world games, but this thing has sucked me in. All the reviews I’ve read use the word “immersive” to describe it, for good reason: I’m just a few hours in but I’m already addicted to period-accurate dice gambling and am getting pretty invested in 15th century Bohemian geopolitics. It’s gorgeous, artfully designed, and runs incredibly well on the Steam Deck.

A shockingly beautiful anime about death

I’m not really a big anime guy. I grew up on Dragonball and late night Toonami, and otherwise never sought the stuff out. But the online praise for Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End was so over-the-top that I was like, “fine, I’ll give it a shot,” and—I kind of can’t believe how good this show is? Without spoiling too much, it’s set in a sort of Lord of the Rings fantasy world with elves and dragons, but the story picks up decades after the big bad guy has already been defeated by a party of heroes. All I’ll say is: It’s a beautiful story about how one day we’re all going to die. And the English voiceover version is really good. I’ve been watching on Crunchyroll, but the the show’s coming to Netflix on March 1st.

That’s it for this week. I guess I’m gonna log into Crunchyroll and watch Reborn as a Vending Machine, I Now Wander The Dungeon.

I’ll see you next Friday.

There’s this famous Marshall McLuhan quote about the way humans work to spread computers and machines: “…Man thus becomes the sex organs of the machine world just as the bee is of the plant world, permitting it to reproduce and constantly evolve to higher forms. The machine world reciprocates man’s devotion by rewarding him with goods and services and bounty. Man’s relationship with his machinery is thus inherently symbiotic.”

It’s a wild quote—and no doubt McLuhan was trying to be provocative (the quote comes from an interview he did with Playboy Magazine in 1969). But if you take McLuhan’s “machines as plants, humans as bees” metaphor seriously, it’s tempting to see video games as the sweet-smelling flowers of the chipmaking industry. Beneath the sun-drenched rose petals, the machine hums. And we buzz—generations of people funneling money into games to spread the seeds of the machine world.

Brilliant post, thank you.

Where do Angel's fall into this, if at all? I'm on the edge this year, and weighing all options.

Oh wow. I also work for a VC firm here in Aus, consult to them. Are you in the games team or another specialty?

Been meaning to look into how the Aus scene is completely devoid of VC for games — I believe most are funded with grants from various State Governments.

Thanks for another interesting read that hit a bit closer to home for me than usual.