UFO 50 and the Lamentations of Khakheperraseneb

push to talk #41 // can video games unlock new possibilities by inventing an alternate past?

This week’s newsletter is an unusual one. Along with some thoughts on the new game UFO 50, I’m sharing an unpublished essay from 2014 which was originally intended for the print edition of Edge Magazine.

Push to Talk is primarily a newsletter about the business of making and marketing video games. But the real reason I’ve pursued a career in games is because I believe they’re a beautiful art form—so I’d love to get away with occasionally publishing more creative and strange pieces like this one.

The following essay is about how game developers might unlock new ideas by embracing self-reference, recursion, and games that only exist in the imagination.

I hope you dig it.

A New Game Made of “Old” Games

The pitch for UFO 50 feels like a prank. Fifty new games, released all at once?

But it’s no joke: Seven years after it was first announced, a small team of indie devs led by Spelunky creator Derek Yu has released a collection of 50 original games—real games, not minigames—all of which could have conceivably been full releases on an 8-bit game console.

Part of UFO 50’s charm is the imaginary backstory Yu and his team developed for it. According to snippets of lore included in the collection, these games come to us from an alternate-history universe where a company called UFO Soft produced a console called the LX during the 1980s.

Each game in the package includes a fake release date and fictional information about its developers. There are even in-universe connections between the games. Several titles have playable sequels, and there are games released “later” in the timeline that build on the designs of “earlier” games—it’s a ridiculously ambitious game about game design itself. Taken as a whole, it’s a work of art.

But in a world where there are too many great games releasing each year, a fair question you might ask when confronted with UFO 50 is: Yeah, but are these games actually good? Is any of this worth my attention?

My honest take: not all the games are gonna hit for you. But the vast majority are fun and imaginative, and a surprising number are genuinely special. Some—like my personal favorites Mini and Max, Golfaria, and Valbrace—absolutely sparkle.

As a result, UFO 50 is crushing it with reviewers, with a score of 92 on Metacritic (aka “Universal Acclaim”) and a 96% positive rating from players on Steam. It’s not a multi-million seller, but because there’s so much great stuff in the package, it has an unusually sticky engagement pattern on Steam. This game was built for long-tail, word-of-mouth growth.

My favorite review of UFO 50 came from Eurogamer’s Christian Donlan, who wrote a sort of meta-review describing his own process of trying to figure out how to review a game made of 50 games. (He ultimately gave it 5/5 stars.)

UFO 50 is one of those rare games that’s trying to do something so weird and original that it winds up inspiring people who encounter it to think outside the box. By inventing a fake past, it inspires an introspective mindset that results in new insights and ideas.

So I was thinking about all this, and suddenly I remembered this article I wrote a decade ago for the British magazine Edge. The piece was about games which are themselves about games. I’d had this idea that maybe games had reached a moment similar to where novels were at in the 1960s, when the literary postmodernism movement kicked off. (This was in 2014, near the end of my games journalism career, and I was writing a bunch of unpublishable stuff like this.)

Edge had printed a few of my feature stories by this point, and its editors were very tolerant of my increasingly bizarre story pitches, but this one was a little too out-there. After beating up the draft a few times and trying to make it work, I withdrew the piece and forgot about it—until I picked up UFO 50.

Other than some minor edits for clarity, the essay below is presented here as it was written in 2014.

The Lamentations of Khakheperraseneb

To find a new way forward for games, we may have to reimagine the past.

1967

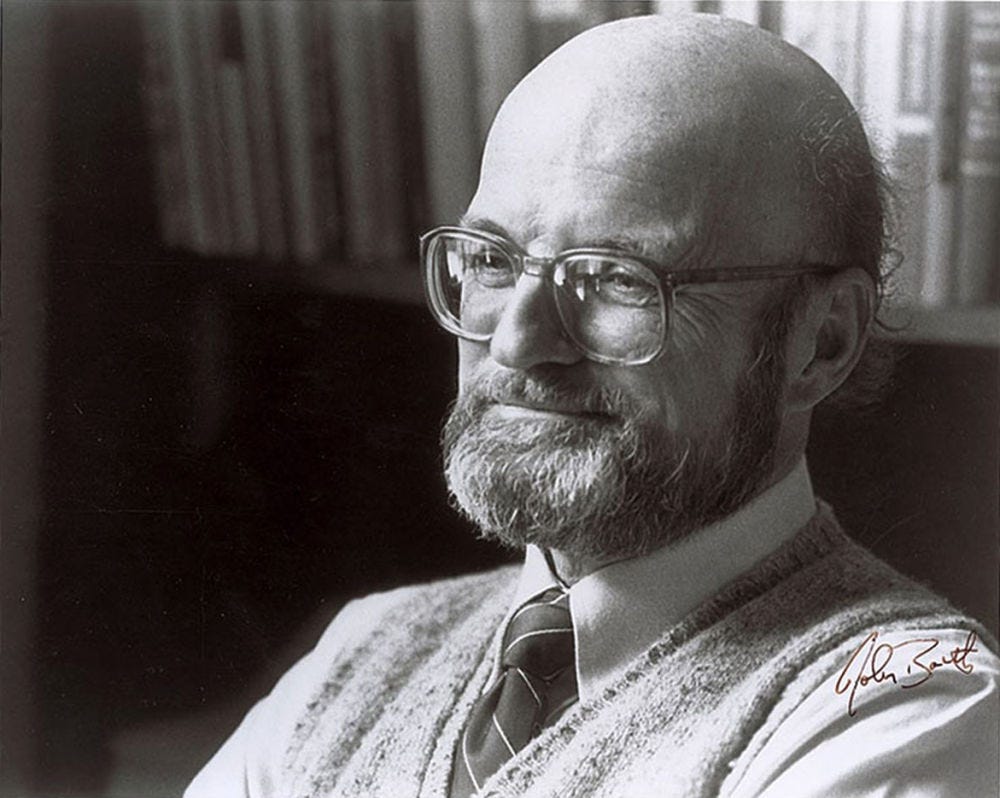

John Barth1—a man soon to become one of the twentieth century's most-awarded novelists—stepped up to a podium and delivered a lecture at the University of Virginia about the state of literature. Barth said he wanted to address "the used-upness of certain forms or the felt exhaustion of certain possibilities."

In his speech, which was published a year later in The Atlantic as an essay titled The Literature of Exhaustion, Barth lamented that far too many novelists of his era were producing "turn-of-the-century-type novels, only in more or less mid-twentieth-century language and about contemporary people and topics." By emulating too closely the style of those that came before (“Dostoevsky or Tolstoy or Flaubert or Balzac”) modern novelists were failing to write truthfully about modern life.

“It may well be that the novel’s time as a major art form is up,” Barth wrote, just as history left behind the “classical tragedy, grand opera, or the sonnet sequence.”

But, Barth argued, there was reason for hope. Writers like the Argentine short story author Jorge Luis Borges had discovered a way to innovate by writing stories about made-up stories. Borges’s story collections like Ficciones are full of tales structured as footnotes and commentaries on non-existent literature. In the worlds conjured up by Borges, characters take for granted the existence of classic works that only exist in their world, and by responding to these invented works, the characters themselves end up creating new works that actually do exist in our world, as books published by Borges.

By imagining other worlds and the literature that populates them—Borges found a way to write books that were strange and otherworldly. It was like, in Borges’s own phrase: the “contamination of reality by dream.”

Writing about Borges, Barth said that “he confronts an intellectual dead end and employs it against itself to accomplish new human work.”

2013

Chris Hecker stepped up to a podium and tinkered with the settings in Windows Media Player. A crowd of game developers was gathered to see Hecker and others rant about the state of the games industry, an annual tradition at the Game Developers Conference. This rant, the Spy Party creator told the audience, was titled "Fair Use." Hecker stood silently at the podium for the next five straight minutes while, on a nearby screen, a video montage showed AAA developers speaking earnestly about how their games would offer players “something completely new.”

In recordings of the GDC talk2, you can hear the audience giggling at footage of a Modern Warfare producer struggling to explain how a heavy Humvee door added emotional weight to the game's narrative, then cheering and laughing as a Killzone 4 producer explains to Jimmy Fallon that the increased memory in the "supercharged" PlayStation 4 would give game-makers "space to develop these characters that you'll truly care about."

Hecker concluded the video with a short clip of first-person-shooter gameplay from Bungie's then-upcoming game Destiny. In the clip, longtime Bungie composer Marty O'Donnell declared "we're creating something completely new." The clip repeated five times, and Hecker walked off the stage. He hadn't spoken a word, but he'd made these developers—so certain of the originality of their work—look silly, simply by allowing them to speak.

The unspoken implication, of course, was that these devs weren’t really doing anything new. They weren’t pushing the medium forward. Their games looked like highly-polished imitations of games that had come before. They had reached, it seemed, an intellectual dead end.

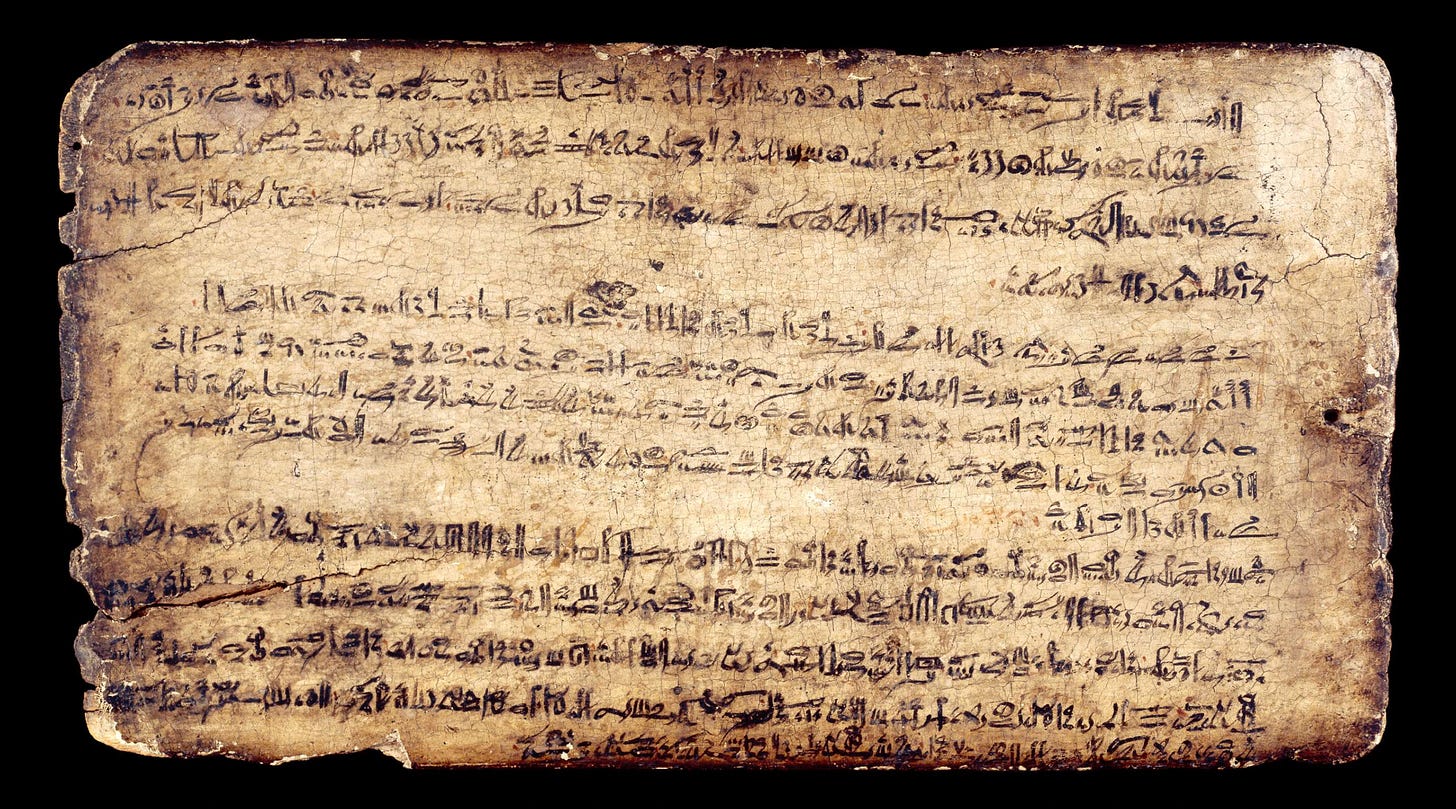

The Lamentations of Khakheperraseneb

Artists have fretted over the "used-upness" of their medium of choice for thousands of years. In 1900 BCE, an Egyptian scribe and poet named Khakheperraseneb lamented the difficulty of writing truly original work:

"If only I had unknown utterances and extraordinary verses, in a new language that does not pass away, free from repetition, without a verse of worn-out speech spoken by the ancestors!" Khakheperraseneb wrote.

Peppered throughout the history of any art form, there have been moments when artists began to worry that all the best work in their field had already been done—that new works are nothing but shadows cast by the monumental achievements of the old masters.

A funny thing tends to happen, then. The art, newly self aware of well-trodden ground, necessarily becomes self-referential. And self-reference in art has a strange power. It can reinvigorate old forms.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra wrote Don Quixote as a parody of the romantic literary stories that were popular in his native Spain at the beginning of the seventeenth century. In his novel, the "quixotic" hero Don Quixote reads one too many chivalric novels and becomes a man possessed, deciding that it is his calling in life to revive chivalry itself. It's essentially a story about the danger of taking stories too seriously.

Any creative form, even the lowly field of advertising, can be invigorated by self-reference. David Foster Wallace once observed that “Advertising that makes fun of itself is so powerful because it implicitly congratulates both itself and the viewer (for making the joke and getting the joke, respectively)."

So what happens when video games become self-aware?

The first time you boot up the mobile hit The Simpsons: Tapped Out, a short animated film plays, setting the stage for the game. Homer Simpson sits at his workstation, playing a mobile game on a tablet device.

"This happy little elf game is so stupid," Homer grumbles. "You tap and wait and tap and wait, and for what? So your pretend town can have more pretend flowers than your pretend friends?" He rolls his eyes. "What a colossal waste of time."

Despite his misgivings, Homer becomes so engrossed in the game that he ignores his duty and (somehow) causes a nuclear blast that levels Springfield. The camera pulls back and suddenly Tapped Out begins to look a lot like the game Homer was playing on his tablet. It is, it turns out, a "pretend town" game.

"It knows that you know that it knows," says Georgia Tech professor Ian Bogost. "But then it just settles into being one of those games. There's micropayments and you can pay $100 for a bowl full of donuts."

This, Bogost argues, is often the case with games that attempt to parody other games. Because the parody is built atop the same foundational mechanics as the game it's referencing, the parody slides into mere mimicry, then morphs into outright emulation.

Bogost's own Cow Clicker, which stripped down and parodied Farmville, was an early example of a game that turned a critical eye towards its own form, but it was by no means the first.

One of the earliest instances of self-reference in games was in the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy text adventure. Games researcher Jesper Juul has fond memories of that game's tendency to joyfully point out its own design elements to the player. "There are footnotes in the game," Juul explains, "and you click through, and some of them aren't even about objects in the game. One just says, 'Isn't it fun reading through the footnotes?'"

Juul points out that this was likely a stylistic carry-over from the Hitchhiker's Guide books, which is in part about other science fiction literature. "It has this running commentary on the future, wisdom, the truth, aliens, blah blah blah," Juul says. "By necessity that had to carry over to the text adventure. That's part of the makeup of the story, that it has to parody the form that it's in."

Throughout the history of games and game genres, self-reference and parody seems to only appear when a genre or gaming trope has become worn out, or at least very well established. The Hitchhiker's Guide text adventure game was released in 1984, just before text adventures were uniformly left behind by devs in favor of graphical adventures. The infamously self-aware Psycho Mantis boss fight in Metal Gear Solid appeared 13 years after millions of gamers had stomped Bowser in the original Super Mario Bros.

In Juul's reading, Portal is another game about games because it toys with the established trope of the progressively harder puzzle game which rewards players for incremental increases in ability. "In a way it was about the video game test lab setup being kind of evil, with GLaDOS assuming the role of designer of the puzzles," Juul says.

GLaDOS acts incredulous each time players make it through one of her test chambers. She, the puzzle designer, thinks you're an idiot, and thus when players reach the end of the game and are tasked with destroying her, it feels okay. "It's completely called for," Juul says.

The paternalistic relationship between puzzle designers and puzzle players is clearly not a surface-level theme in Portal, but it's there, permeating the experience. There's an underlying self-awareness in the game, and it leads directly to the moment at the beginning of the final act, when players literally break through a (fourth) wall and escape the trappings of what was previously "just another puzzle game,” albeit a brilliant one.

In one sense, Portal couldn't exist except in response to other, less self-aware puzzle games, in the same way that The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy couldn't exist except in response to other works of science fiction. In responding to other games, some games do manage to become something other than "just another one of those games."

Don Quixote proved it in 1605: self-reference can serve as an incredibly fruitful starting point.

Lost in the Funhouse

John Barth's "The Literature of Exhaustion" is now recognized as the quasi-official manifesto for literary postmodernism.3 The loose grouping of novelists in the postmodern school includes Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Thomas Pynchon, Kathy Acker, David Foster Wallace, and Barth himself, who released a mostly postmodernist collection of short stories, Lost in the Funhouse, just a year after The Atlantic published his now-famous essay.

In later years, Barth admitted to feeling frustrated by the fact that some had interpreted his essay as a “death of the novel” piece. In reality, he was trying to argue for a new path forward. As he wrote in the essay: This problem plaguing literature, this used-upness, was "by no means necessarily a cause for despair."

But despair is exactly what Chris Hecker says he feels when he thinks about developers claiming that a first-person shooter is "something completely new." Until now, Hecker has kept his silence about what he meant to imply about the state of the games industry in that video he showed at GDC 2013. Hecker says he worried if he talked about it, "the true depths of my despair for the state of the art form would have been revealed." Hecker then catches himself: "Actually, this is not exactly right… it's more like my despair at the gap between what we say we've accomplished versus what I feel we've accomplished when I actually play games."

Although Hecker sees parallels between Barth's essay and his own "silent rant," he wishes these parallels ran deeper, because he believes that there's a significant gap between the place literature had made it to in 1960 and the place games have reached in 2014.

Hecker prefers to compare the history of games to the history of movies—another relatively young medium. "Yes, there have been some great games," Hecker says, "but they are great games in the way Fred Ott's Sneeze is a great film: incredibly important historically, a vital exploration of the new form, but not anything that resembles modern films or really spoke to the human condition. It maybe whispered about the human condition."

This, Hecker acknowledges, is a cynical view of the history of games, but he argues that it's also a highly optimistic view about their future. His cynicism is couched in a belief that the games of the future will make the best games of today look like "quaint historical artifacts."

Seventeen years after writing "The Literature of Exhaustion," John Barth republished the essay in a collection and included a new introduction to the piece. Like most artists revisiting an old work, he found flaws in his younger self's efforts: "Its urgencies are dated; there are thin notes in it of quackery and wisecrackery that displease me now," he wrote.4

But Barth stood by the essay's main argument: "That virtuosity is a virtue, and that what artists feel about the state of the world and the state of their art is less important than what they do with that feeling."

That’s it for this week. I’m gonna go make like an Egyptian poet and engrave a bunch of my complaints on a wooden tablet.

I’ll see you next Friday.

Back in 2014, when originally reporting this story, I thought it might be fun to try to get in touch with John Barth himself to get his thoughts on video games. His email wasn’t listed anywhere online, so I pinged a few people at John Hopkins University, where Barth had taught from 1973 until his retirement in ‘91. It didn’t look like that would lead anywhere, but after just a couple of days I received an email:

“Your request for an interview has been passed along to me,” Barth wrote. “I appreciate your interest, but have retired from interviewing, among other things.” I sent him my thanks, but then tried to slip in just one quick question. Again, Barth demurred, but the phrasing he used has always stuck with me: “I'll pass, at least until & unless my drowsy Muse unhibernates.”

John Barth died on April 2, 2024, age 93.

You can watch the Hecker talk here. It kicks off around the 5:00 mark in the video.

Literary postmodernism and philosophical (or political) postmodernism are mostly unrelated and shouldn’t be conflated.

I feel that.

I don't have anything to add to this newsletter, I just want to say I love your work and I'm glad you're on Substack!

never stop writing