The Gamers Are Locked In

push to talk #39 // players are hooked on games that launched a decade ago // what does that mean for the industry?

Last week’s newsletter discussed data showing that the vast majority of playtime is now spent on older games. This week’s post is a deep-dive followup.

Read part one: Are Old Games Killing New Games?

Back when I worked on League of Legends, we had this huge segment of the audience that basically hated the game—and us—but were never going to stop playing.

This was like 2015–2018, mind you, and League launched in 2009, so some of these people had been playing for the better part of a decade.

We called this most feisty, salty segment of the playerbase “grizzled veterans.” I don’t think that was something we made up. Maybe it came from a marketing consulting group? You know, the kind you pay some ridiculous fee to come in and produce a slick PowerPoint deck.

Anyway, the grizzled veterans were super vocal—the type of people who’d go on r/leagueoflegends and post a screed because you took 5% off the AP scaling on Vel’Koz’s Q. (If you’ve never played League, I promise that sentence makes sense.) The grizzled vets could be pretty mean and cynical at times.1 But they also played consistently, making them really important for the game’s health.

The interesting thing about the grizzled veterans segment was that it was growing, in raw percentage terms. As time went on, more players aged into the grizzled vets type. If it was once only 20% or 30% of the playerbase, I have to imagine that by now, at least half of all League players fit this type.

A growing slice of the League audience, in other words, are players who have found their “forever” game, and who seem to be permanently locked in.

I worry the same thing might be happening to the entire games market.

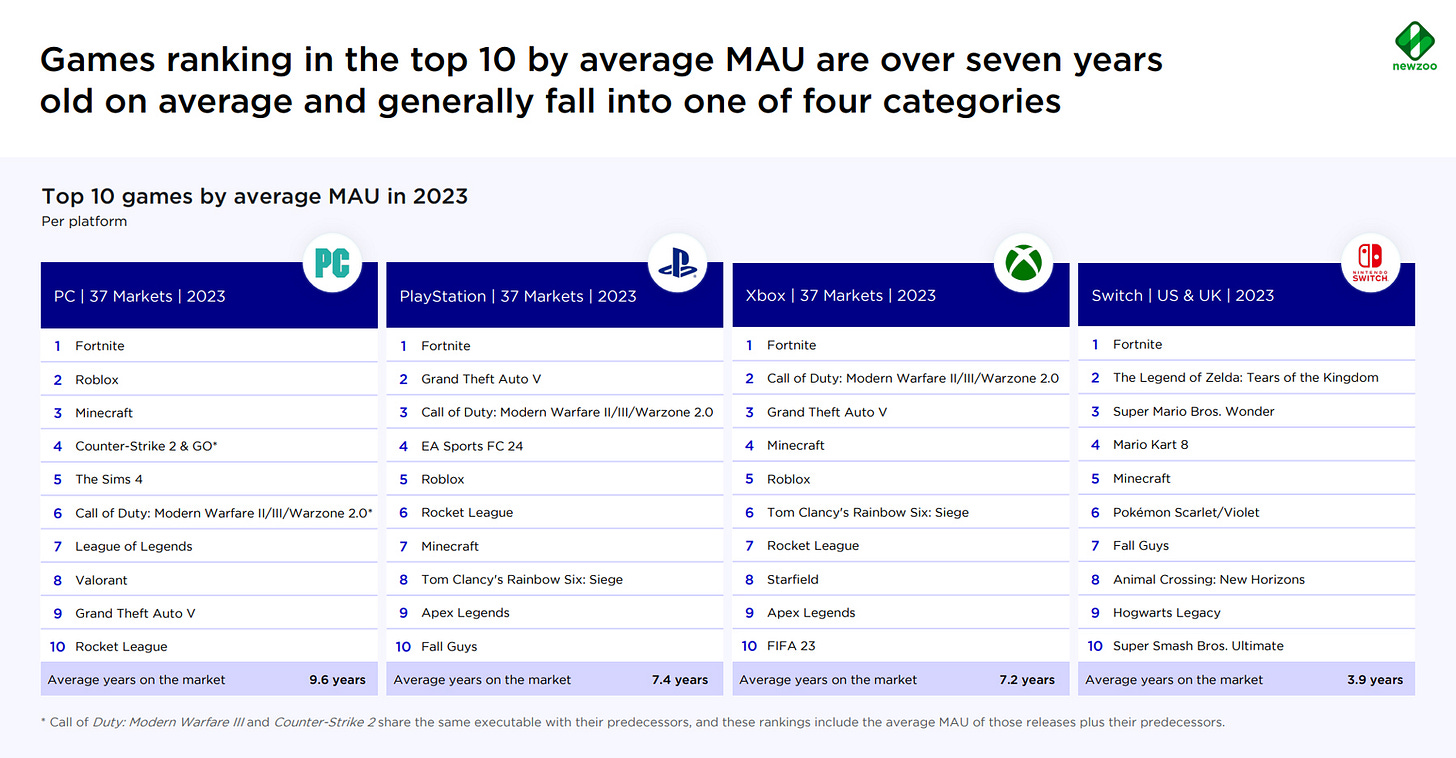

I can’t stop thinking about those Newzoo charts from last week’s newsletter, the ones that showed how the vast majority of gaming hours are getting spent on old games—in many cases games that came out over a decade ago.

What percent of the overall gaming audience is composed of these “grizzled veterans” who are completely locked in on a game from a decade ago? Are they even really part of the “gaming market” anymore? Or are they effectively inaccessible to devs making new games?

Here’s my hypothesis:

There’s a huge percentage of gamers that put the vast majority of their gaming hours into one title. In no particular order, probably one of the following: Minecraft, Roblox, Dota 2, Final Fantasy XIV, Counter-Strike 2, Warframe, Fortnite, PUBG, CoD, Rainbow Six Siege, Rocket League, Escape From Tarkov, Rust, League of Legends, Apex Legends, War Thunder, Destiny 2, Teamfight Tactics, Diablo IV, VALORANT, Madden, FC (né FIFA), NBA 2K, Brawlhalla, World of Warcraft, Overwatch, Genshin Impact, Monopoly Go!, The Sims 4, GTA V, Brawl Stars, Clash of Clans, Royal Match, Candy Crush, Old School Runescape, Elder Scrolls Online, Chess.com, orWordle.

These are the top games I could think of with massive locked-in audiences. Of the 38 listed, only six—VALORANT, Diablo IV, Genshin Impact, Monopoly Go!, Royal Match, and Wordle—are new titles that launched this decade, and those are mostly mobile games. (I’m sure I missed a bunch of other mobile titles, because I do not care about them.)2

The rest are very old live service games or long-running annualized franchises.

So there’s a lot of players that are locked in on their “main” game. But I’m pretty sure they almost all dabble. When a hot new game comes out, these locked in players use it as an opportunity to take a little vacation from their main game. They dip into the new experience, goof around for a month or so, and then go back to the old ball and chain feeling refreshed.

This pattern works out really well for premium-priced games. Games like Helldivers 2, Black Myth: Wukong, and Palworld make a killing off of these “locked in” players because they’re able to get their money during the small window they hang around.

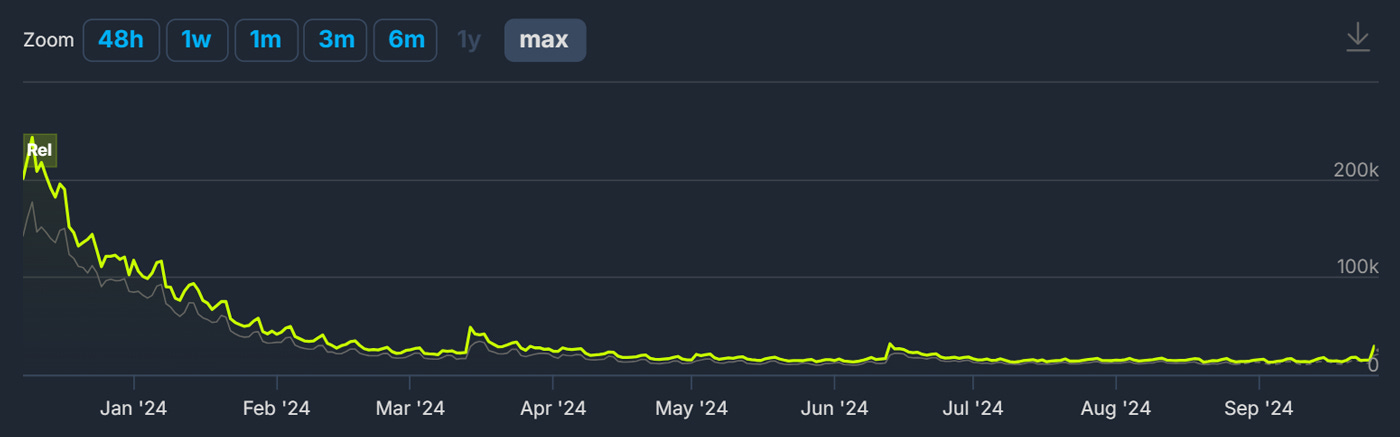

For free-to-play live service games, however, it’s a different story. These games’ experience with the locked-in vacationers is one of sugar-rush excitement followed by devastating disappointment as they see a massive opening-day spike in players that quickly dissipates.

If true, this could explain why we’ve seen so many premium games succeeding in dramatic fashion this year, while basically every live service F2P game has been a flash in the pan.

Without naming any names, here are daily peak concurrent player charts for some big-name free-to-play PC game launches from within the past few years, courtesy of SteamDB:

To me, this reads as huge influxes of players trialing each of these flavor-of-the-month games, followed by their inevitable return to… whatever they were playing before. Most get their kicks in for barely a month before bailing. By month three, the majority have moved on, never to return.

For a premium game, charts like the ones above are fantastic news. Numbers like these translate into tens of millions of dollars, at minimum. But these are free-to-play games. And for F2P games, charts like the ones above are a death sentence.

Let’s recap:

There’s a bunch of old live service games that are very sticky

But their locked-in players often dip out for a hot sec to try out new games

For premium games this engagement pattern is fine, because devs get paid

But for new live service games (mainly F2P ones) the pattern is deadly

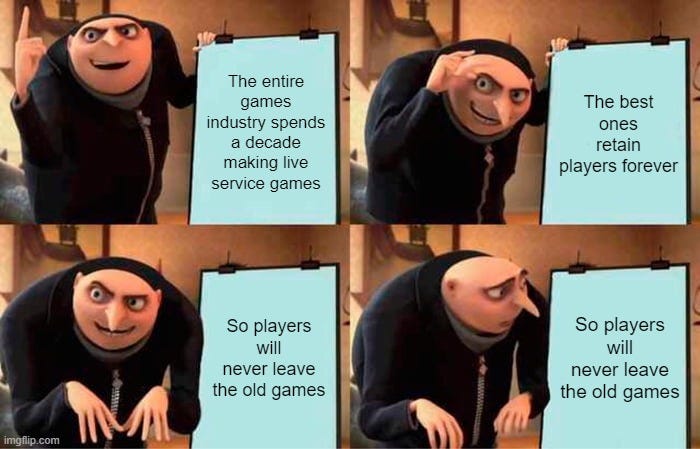

The fact that all these old live service games are so sticky was, of course, a huge part of their appeal for game developers in the first place. Game dev has traditionally been a hits-driven business, not unlike Hollywood (or book publishing or the music industry in its heyday for that matter). But if you can create a successful live service game, you can build a stable business around it. And if you make a really successful live service game, you might even have enough money to get rich and hire all the best talent and build a giant campus with a coffee shop and a movie theater and free snacks and a water fountain/basketball court. So it’s tempting.

There are also a surprising number of live service games that just modestly chug along, making… well, not water fountain/basketball court money, but really great money. Take Elder Scrolls Online for instance. Last week a former ESO UX Lead’s LinkedIn profile made news by letting it slip that ESO has made $15 million per month for over a decade. That’s a ridiculous figure, but it lines up with the officially-reported figure of $2 billion lifetime revenue. That’s real money. That’s like… Skyrim money. So it was far from crazy for devs to spend so much of the 2010s making these games.

But now we’re nearing the halfway mark for the 2020s, and only like maybe three new live service PC and console games have enjoyed anything like the level of success once enjoyed by a game like Elder Scrolls Online. And two of those three games have Chinese owners and access to the enormous Chinese games market (VALORANT = Tencent and Genshin = miHoYo).

There are a ton of questions you could ask about the Locked-In Gamers phenomenon. But the main one that jumps to mind is:

Why do so many players get so locked in to these old games in the first place?

Because I’m a shameless corporate ghoul, I actually posted a variant of this question on LinkedIn. Some smart people responded.

My favorite response came in from independent game dev Graeme Kennedy:

I love this, and think Kennedy is absolutely right to focus on the equity players build up with these games and the pain that leaving would cause them.

I’d add a fifth “Sticky Factor” to Kennedy’s list, which is institutions and infrastructure. Things like really big competitive scenes with regularly recurring tournaments (think Worlds for League of Legends or ALGS for Apex) develop an out-of-game scaffolding around a game that can make these live service games rewarding to stick with for a long time.

But institutions and infrastructure don’t have to be built around tournaments or organized competition. BlizzCon is (was?) an institution that served a similar role for WoW players. Any kind of community can become an institution if it grows big enough. Healthy content creator ecosystems function like institutions and generate onboarding infrastructure for new players. The mod community that grew up around Minecraft is almost certainly one of the best examples of this in practice.

So the sticky games are sticky in an almost overdetermined way.

That raises the natural follow-up question:

How do players ever get un-stuck from these games?

On the one hand, it feels obviously true that every game loses its players eventually.3 Games do decline. But for those that reach very large scale sustained success—just to pick a number, let’s say over 250k daily active users for at least a couple of years—it’s not obvious that these are destined to ever fully die out. It’s possible they’ll hold on to a big chunk of their playerbase indefinitely, and even to enjoy occasional resurgences and new all-time highs.

Over the past week, I’ve talked with about a dozen or so game developers about this question, and what factors might cause players to quit a “forever” game.

A few common themes have emerged:

1. A new game introduces an exciting new genre combination or a huge technical advance on the genre

It’s possible that Valve’s Deadlock is doing this for Dota 2 players. It really is just Dota 2 in a third person shooter context, and it works way better than it should.

I don’t expect it to take all or even most Dota 2 players, but there’s some evidence that it’s at least a little bit cannibalistic.

There are a ton of other examples of this happening, the most obvious recent one being the fractal explosion of the battle royale shooter genre after the launch of PUBG. First Fortnite grew the genre and took some players with its building mechanics and more welcoming vibe, then Apex came charging in and captured imaginations with its wild movement tech and hero-based abilities. Call of Duty: Warzone successfully reimagined CoD’s TDM-focused gameplay in a BR context.

All of these games succeeded in part by taking players from the other BRs, though none of them killed PUBG—far from it, the game’s still thriving. Instead, they each found a different slice of players and nibbled away at that niche while simultaneously growing the overall BR shooter market.

2. Every game is actually competing against all possible forms of entertainment

This is a cliché, but it’s true. TikTok and Netflix are the biggest competitors for a game like Fortnite. If Discord’s new foray into games pans out, it could become a threat to a lot of big more traditional live service games.

You can actually track this factor by keeping an eye on those gigantic Nielsen type surveys of “how teens spend their time.” It’s the most boring answer but for live service games in particular it really is a war of all against all for attention.

3. Aging out

This goes undiscussed because it’s so gradual and hard to identify in the data, but changes in life circumstances or responsibilities are probably one of the more powerful forces for un-sticking players from “forever” games. My wife and I both aged out of Teamfight Tactics because we have three kids. It’s been more than two years since she played a video game of any kind.

I’ve talked to a lot of people about how Roblox might be affected by players aging out. For at least half a decade I’ve heard game developers casually talk about what happens when the Roblox kids “graduate” from the game to play more serious titles. I do think it’ll happen eventually, but it’s not obvious to me that all of them will graduate to other games. At least some portion of them are going to decide they don’t actually care that much about video games.

That might sound a bit heretical. The games industry has spent a good ten or fifteen years patting ourselves on the back and repeating the mantra that “everyone is a gamer now” because we saw our moms were getting into Words With Friends. But it wasn’t actually true that everyone is a “gamer,” in the sense of being someone who plays games, plural—a lot of people play one game until they get tired of it, and move on without seeking a new gaming fix.

People who once played lots of games as kids can and do grow up into teens or adults who play basically no games at all. That’s at least half the dads in my neighborhood: “Yeah, I used to play Madden and Call of Duty but now I just don’t have any time.”

4. The game becomes its own worst enemy

Everybody who has played or operated a live service game has seen their active player count take a dip due to mistakes made by the devs:

Accumulating pain points that go unaddressed for too long

An unpopular approach to balancing or monetization drains the fun for players

Tech debt piling up and causing the game to become literally unplayable for some players

Failing to evolve in interesting ways

Or evolving in a way that turns off longtime players

A disproportionate amount of discourse from players about live service games tends to emphasize these reasons for playerbase declines, and I do think there can be some merit to that. But more often games lose players because of the other three reasons listed above.

Almost any “bad change” to a game is reversible. Changes to the overall games market are not.

That’s it for this week. I’m gonna go run a Google search for “how to create a forever newsletter.”

I’ll see you next Friday.

I kinda loved the grizzled League vets. In truth, I owe them—a big part of the reason I ultimately got promoted to LoL communications lead was because I was one of very few Rioters at the time who was willing to go into the Reddit salt mines and take some licks on behalf of dev teams. (This was especially true around 2016, during the “dynamic queue” debacle.) The viciousness of the grizzled vets was an opportunity. I’d log on to Reddit, jump into spicy threads with sincere responses on issues people were having, and then crack a few jokes. Although these people were often pretty unreasonable in terms of their tone, and sometimes they just wanted a punching bag, you could win a lot of them over if you showed genuine care, delivered honest answers, and had a sense of humor.

Sorry!

Except for Old School Runescape, I guess. Not even Runescape 2 could take players from Runescape.

Been unable to catch these for a bit, but I'm not surprised I've come back to another banger article.

Topically, I've defaulted back to a lot of my old comfort games, namely Team Fortress 2. The past few weeks, when I've finished with work for the night, I'll play a few casual rounds of payload. (Is there any other way to play?) I wonder if, for a lot of us well into adulthood and/or middle agedness, there's also some aspect of "playing the old songs and watching the old movies," so to speak? These games don't just hold entertainment and familiarity, but also memories of times gone by with friends that we might not see or have as much time with anymore.

A lot of us who grew up in the middle of the console generation that really started to push more and more into the mainstream grew up not only with the great games of the time, but also many that were just before. Folks are STILL making youtube videos about SNES and Genesis games, or weird PS1 games, despite those being covered many times even as much as 10 years ago, and yet people are still going back to revisit the classic and the novel from those libraries.

As an aside, I wonder if the blurring together of the different consoles and personal computers, of few exclusives and even of generations, as games continue to be re-released or backwards compatable, has fundamentally changed the way that people currently think of games? No longer a limited library constrained to a piece of hardware but instead an endless ocean of variable depth and quality.

So many thoughts and so much work to do that is keeping me from writing an essay, but a very long story short - video games are kind of morphing into what tabletop games have been for decades. Graeme's list, and your fifth addition, match up with a lot of my experience in watching games like D&D, Magic, Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh, and Warhammer dominate their categories in tabletop year after year.