Games Marketing on Easy Mode, Hard Mode, and the Dark Valley Between

push to talk #23 // on marketing difficulty settings and regrettable tweets

Before we hop into this one, a quick editor’s note:

For the next two months I’m going to alternate every other week between original essays focused on game marketing and more traditional Push to Talk posts with the usual news links section and interviews.

Today’s post is a sort of conversational essay based on some ideas that have been boiling in my mind for a long time. It also includes an interview with some game devs who went viral this week with a controversial tweet.

That’s below.

Games Marketing on Easy Mode, Hard Mode, and the Dark Valley Between

I spend a lot of time looking for marketing ideas worth stealing.

This is what a lot of marketing is, right? You pay attention to what the herd is doing, and if you see somebody breaking away from the pack and doing something interesting, you go take a look. What do they know that I don't?

One person I'm constantly stealing ideas and inspiration from is Victoria Tran. Even before her current role on Among Us, she's always been doing really weird and interesting campaigns—her hilarious email marketing campaign for Boyfriend Dungeon is one of the first ones that really captured my imagination. But she's done dozens.

Tran is also the rare sort of person who gives away lots of ideas for free (which is why you should subscribe to her newsletter). Not everybody is so open.

Sometimes you've got to go snooping for inspiration. And when you do go snooping, you will very often find something amazing.

It's this: almost nobody has any original marketing ideas.

It’s a pattern that repeats over and over. A hot new game comes out of nowhere and starts pulling in tens of thousands of reviews or concurrent players. So I'll try to reverse-engineer their go-to-market plan to see if they did anything weird or interesting on the marketing front.

And, I swear, most of the time the answer is not really.

Even for games that popped off hard, most successful game devs are following the exact same GTM playbook.

The Hit Game Marketing Playbook

Particularly if we focus on successful PC games, most GTM plans look basically like this:

Make a great Steam page >6 months before launch to gather wishlists

Have excellent, grabby trailers and screenshots

Try to go viral on social with gameplay footage and memes

Build an email list and a Discord channel

Do some private playtesting to build a core community

Enter festivals and showcases

Launch a demo alongside a festival or showcase

Go into either Early Access or full release with >50k wishlists

Share the game with a ton of streamers and hope some pick the game up

Pray for stable servers, positive reviews, and word-of-mouth growth

Simple right? Well. Here’s the problem: This isn't just the playbook for games that popped off. It's also the GTM playbook for plenty of games that flopped hard. Which is to say, it's the playbook everybody runs.

Or, at least, it's the playbook everybody tries to run.

The playbook only works if your game is highly appealing, which is just a stuffy way of saying that people see a 10-second trailer of the game and they go YOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO that looks siiiiiiiiiiick!!! Or something similar.

A game either has it or it doesn't. I recently posted a trailer for a game in my company Discord channel and all the replies looked like this:

I'll talk a little bit about that game later. It's an upcoming title, so we don't know it'll be a hit, but I think it's almost guaranteed. The point is, it has that first-glance wow factor.

There are other ways for games to pop off. Sometimes—as we all know well—content creators have so much genuine fun with a game that it blows up despite the devs doing almost nothing else from the playbook.

One of the funniest recent-ish examples of this is Dark and Darker.

When they first started really popping off on Steam, I dug through all their social accounts—their Discord, website, replies to Steam forum threads, everything. And I started getting really pissed off, because these guys were doing nothing special, and yet everything was working out great anyway.

They were just running occasional weekend playtests on Steam, announcing them a couple of days in advance with a Steam blog and a tweet. No fancy assets. No billboards. No music videos. Just tweets and blogs.

And they were cracking >100k concurrent players on their playtests.

They didn't have to fight for attention, or post banger TikTok memes, or pay streamers millions. All they had to do was occasionally turn on the game, and watch the players pour in.

Dark and Darker is simply so freaking good that, when it comes to marketing, the devs were playing on easy mode. (Well, you know. Until the lawsuit stuff.)

This, finally, is where we begin to arrive at a hypothesis for how game marketing difficulty levels work.

Sometimes, for whatever reason, a game possesses qualities that make it bang when marketed. The trailers go viral. Content creators play it without being paid. Players come begging to join playtests. That's marketing easy mode.

And sometimes, it feels like no amount of marketing in the world can help a game. That's hard mode.

Or, as a wise man once put it:

I'm sick of people tellin' people I'm here 'cause of marketing dollars. Oh. You think that everything is gonna blow just 'cause you market it harder? No. —NF, NO NAME

But between these two extremes, there is an enormous gulf—a dark valley.

If you're in the dark valley, it's hard, terribly hard, to know where exactly you reside along the spectrum. But if you're in easy mode or hard mode, there are impossible-to-miss signs.

So today, I want to talk about two examples:

One game that's obviously playing on marketing easy mode.

Another that's struggling atop the most frigid peaks of hard mode.

Most games—even many really great games—reside in the dark valley between these two points. Some parts of marketing come naturally, and some are a struggle. Sometimes you have a game that’s an absolute joy to play, but that joy is difficult to communicate with a trailer, or people have to sink their teeth in for an hour or more before it all really clicks. This happens a lot!

So I don’t want you think that when I say “marketing easy mode” I’m referring only to great games, or that when I say “marketing hard mode” I’m referring to bad games. That’s not the case.

Both of the games I want to talk about today are cool, worthwhile artistic works.

But I want to look at them critically because I think they serve as coordinates on a map that can help game developers think honestly about how hard it’s going to be to market their games.

Marketing Easy Mode: Screenbound

The true differentiator between the “pop off” games and DOA duds is that for the big hits, every stage of the process feels weirdly easy.

This is something I've been thinking about a lot ever since I interviewed the creators of Screenbound for a guest post on my friend Chris Zukowski's blog.

Screenbound, which you've almost certainly already seen, is being mostly made by these two awesome guys who've been working on games for a long time—one of them has published over 100 games, mostly on mobile. And they seem sort of flabbergasted by how easy every step of the process on this game has been.

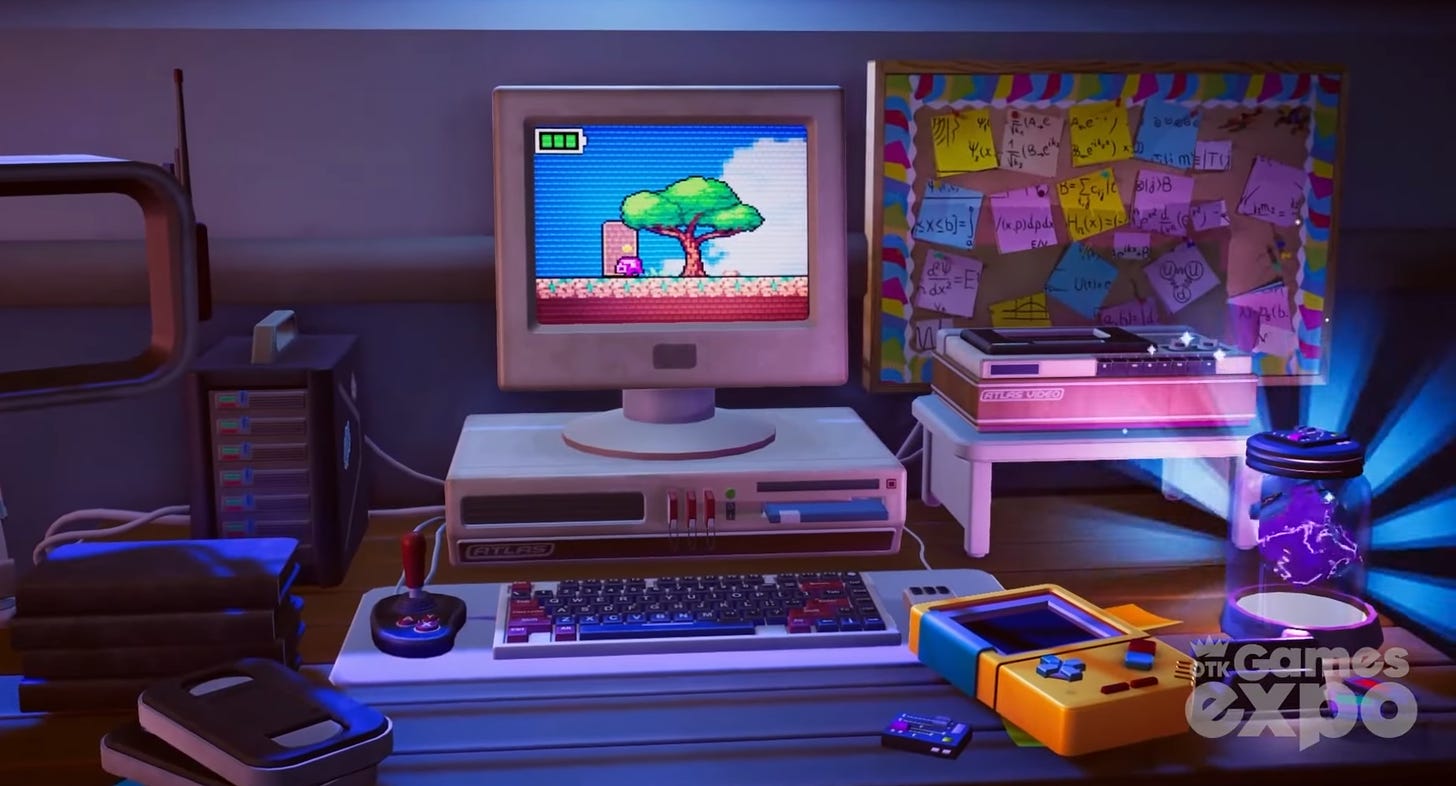

The first gameplay video they posted of Screenbound on TikTok went more viral than any other video in the history of their account. Same thing with a ton of their tweets. The game's core premise—play in an interconnected 3D world and a 2D world at the same time—is just so irresistible that basically any time they post a new clip it bangs on social.

“I was kind of confused,” Presseisen said, of the reception Screenbound got on social, “because it was 100 times more than any of my other games. I was like what the heck. And then I would post a new thing and it would get even bigger and just kept snowballing.”

The same thing is working in their favor with festivals. The Screenbound guys told me that they're included in six separate showcases and festivals this month, including Day of the Devs and the OTK Games Expo, the latter of which had about 150,000 concurrent viewers on Twitch. For many, they didn't even apply to join—the festival organizers reached out to them instead.

This is what marketing on easy mode looks like. I’m not saying that making the game is easy, but getting attention… kind of is? The likes come easy and the wishlists come cheap. That's how you know you've got a hit game on your hands.

But as someone trying to market games, what are the actual takeaways from this example? Is it to only make games with a visually fantastic X factor like “play in 2D and 3D in the same time?” That’s not the kind of thing you can slap onto an existing project—these ideas have to emerge from the game’s core thesis.

In that HowToMarketAGame.com blog, I tried to put together some takeaways from Screenbound to explain their success. There are some really smart things those guys are doing, particularly with the way they’re introducing new features into the game’s prototype with an eye for ideas that will make for great social content.

But—let’s be honest—any time you try to explain why anything is successful, you’re mostly just guessing.

The only sure takeaway from the case of Screenbound is this: it possesses qualities that make it vastly easier to market than most other games. When you’re playing in marketing easy mode, you feel it. It’s one of those “you know it when you see it” things.

But what do you do if you’re in the opposite situation, and it’s feeling like nothing comes easily?

Marketing Hard Mode: Veritus

Let’s talk about Veritus. It’s a Zelda-like game.

This week, one of the devs tweeted about it (see above) and bad-mouthed the newer mainline Zelda games in the process. A lot of people saw that tweet, got mad about the tweet, and tweeted about how they’re mad about the tweet.

I’m gonna keep it real with you. On a professional level, I would not advise making a post like the one above. If a dev from my team made a post dunking on Nintendo, I’d have a heart attack. Generally speaking, you just shouldn’t trash-talk the competition.

But on a personal level? Yo… This is hilarious. LMAO.

I’m not saying I love to see it. But it does crack me up when indie devs go out of pocket like this. It’s fun to watch.

But that’s beside the point. Alright? Wipe that smile off your face. We’re talking about marketing. And there are lessons to be learned here.

What really grabbed my attention was what happened next. The Veritus devs got mad, because this self-inflicted controversy was the first time they’d ever gotten a meaningful wave of attention, despite four years of attempting to market the game.

The above reaction from Brendan Steppig—one of the other main devs on Veritus—is so beautifully human. Most people would be devastated if thousands of people online were angry at them. Not this king. He’s mad that his boss’s trolly tweet is what it takes to make anybody pay attention.

Some people tend to view every spicy post or hot take as an opportunity to argue over the moral code of the internet. So the replies to Steppig’s post included a ton of scolding and chastisements. But if you can forget about the extra-spicy original tweet, what you’ll see here is a person being vulnerable and honest about the pain they’ve felt being (mostly) ignored over the past few years.

See, Veritus isn’t the first game that Steppig and MHINBRON have worked on together. They’ve done another retro Zelda-like called Prodigal and a 2D platformer called Curse Crackers. Both have just a couple hundred reviews on Steam, though with ratings averaging in the mid-to-high 90s. Basically, they’ve got a small but dedicated playerbase.

So, when MHINBRON posted that spicy tweet, he was assuming it would only really reach that same audience—after all, they’d never had a viral tweet before.

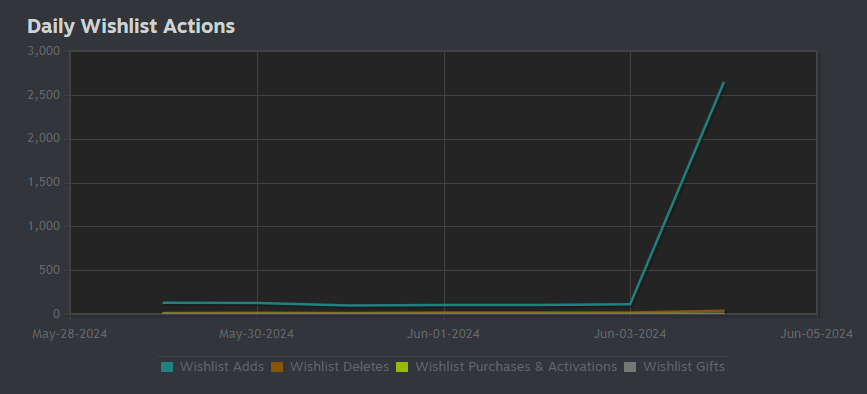

But when it went viral, the impact wasn’t all bad. The day after the controversy, MHINBRON posted to say that the tweet had driven 800 wishlists from Veritus, their biggest ever single-day spike. “I will actively avoid repeating this sort of thing at all costs,” MHINBRON wrote, “but the numbers are still interesting.”

Remember the old rules of Twitter? Each day on twitter there is one main character. The goal is to never be it.

In 2024, does anyone really believe that? We’re entering Q2 of the 21st century, where the goal for a lot of people is to always be the main character. How many grifters, con artists, and attention hogs does that bring to mind? In the “gaming” corner of the internet alone, I can think of at least five that wake up every morning and make a play for main character status. And to some extent, it’s rational behavior, because these people have recognized that the internet is a machine that converts attention into money. The goal is to be it. Get it twisted—this is how the world works now.

But, look, that’s not who the Veritus team is. MHINBRON’s tweet was ill-advised, but it was also clearly a throwaway post intended to be cheeky—not worth a tenth of the pearl-clutching that ensued. And, as MHINBRON and Steppig said repeatedly during the fallout, they had no idea that anyone would even notice. These guys aren’t trolls, or manipulators. They just had a spicy day.

“It's no secret that we're terrible at marketing, you'll get no arguments from me about that,” wrote Steppig on X. “This all has stemmed from a personal post that wasn't ever expected to get more than a handful of likes. It's not some misguided or masterful attempt at viral marketing.”

I saw this, and I started to wonder: Are they actually particularly bad at marketing? Or are they just playing on marketing hard mode?

I have my own theories about why games like Veritus struggle to get attention on social, and we’ll get to those in a second.

First I wanted to hear from Steppig and MHINBRON directly, so I reached out and asked for a quick interview.

A quick Q&A below:

Q&A with the Veritus Team

PUSH TO TALK: In one of your tweets you said that you've heard people say that if they wanted to play a Zelda-like, they'd just go play Zelda. Do you feel like that's a positioning/marketing problem for your game, where people wrongly assume it's EXACTLY like Zelda?

MHINBRON: I think viewing Zelda as a market and not as a fandom is a mistake. Whether that is an opinion I have [come to] over the last 24 hours or before I can’t say for certain. I think they love the titular characters and elements that carry through each game and specifically want Zelda which is why when you try to market as a Zelda-like rather than some degree of action adventure you are setting yourself up for disappointment. We have reached out to many Zelda content creators and only one gave us the time of day. The rest responded with what I would equate with “Lol no, I already have Zelda, thanks.'“

I'm also kind of wondering about what the maximum possible market-size is for 2D Zelda-likes. Sort of a dry biz question, but like what would be the best-case scenario you imagine in terms of sales?

MHINBRON: If I sell 5,000 copies, at the end of the day I’ll be pretty happy. No idea what possible market size there is. I’m just trying to tell a story and get it out there.

Brendan, what's your take on why marketing Veritus feels so hard?

BRENDAN STEPPIG: Well, I'd guess at a few things. The first is that our games as a whole tend to focus on solid—if not flashy—gameplay, building on an existing world, and interacting with the overarching stories of unique characters as they carve out the future of that world.

The second, I think, is that without constant engagement, your reach is only so far. Most of the time it's the same really passionate community members interacting with out post, who, frankly, we owe just about everything we have so far to. Unfortunately unless somebody with some weight is really pulling for you, even one large account weighing in doesn't make much of a difference.

In general though what makes it hardest is a lack of feedback. Either a post does well or does poorly. It's hard to tell if it's the way we're presenting it, what we're presenting, when we're presenting it, or if we're just unlucky that day. We're excited about the whole game but don't have any clue what people want to see from it.

How much do we reveal and how much to we leave for the player to discover on their own? If it's just that our games were bad, we'd rebuild the whole thing from scratch if we needed to, but the majority of player feedback we get is positive. There's also just a LOT of good games out there with a lot more press and industry behind them as well as all the other small teams like us struggling to break out of their bubbles. It's tough to see everything and it's tough to BE seen.

IMO a lot of games discoverability comes down to having a trailer that "WOWs" in the first few seconds. To what extent is that a factor, in your opinion?

BRENDAN STEPPIG: I think trailers are a big deal. People want to be able to see and judge what the game looks like and how it plays. I'm not sure if it needs to "wow", but for me at least it needs to speak to me somehow in that time with a fun little gameplay or story moment. Despite the overall commentary, and whether or not they are genuine about it, even the folks chastising us have largely been saying that they thought the game looked good based on its trailer.

I know you're feeling frustrated because the one tweet to go viral is a negative one (and all that says about the modern internet) but have you had any good come out of the recent controversy? Beyond the obvious awareness of the game.

BRENDAN STEPPIG: In terms of good or bad that's come out of this, it's hard to say so soon. We've absolutely had a dramatic (haha) increase in wishlists, though. Whether that makes much of a difference in the end, it's hard to say, since wishlists only fractionally translate into sales, but it was a jump of several hundred when we'd been trending just a handful at a time.

Some Takeaways

This piece is already trending long so I’m just gonna get to the point. I think Veritus is stuck in marketing hard mode for a few reasons:

Niche Genre - Games like Veritus often struggle to get attention because the genre they’re in is niche, or heavily saturated. Even if you’re making an immaculately constructed retro Zelda-like, your appeal is limited to people who want to play a retro Zelda-like, which is probably not that many people.

Fandoms Aren’t Markets - MHINBRON’s observation that Zelda players are a “fandom” rather than a “market” strikes me as really insightful, and it’s backed up by the feedback he says he’s heard from Zelda fans. It’s possible that Zelda-likes are a kind of cursed genre to work in, because there are no genre fans—only Zelda fans.

Retro Pixel Art: Aside from choice of genre or game mechanics, one of the best ways to grab attention with marketing is with art direction that stands out. 2D pixel art—though a totally reasonable artistic choice for the genre—doesn’t help you stand out from other indies.

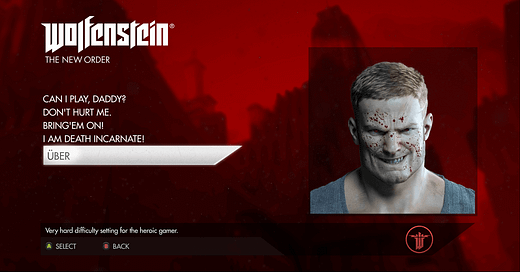

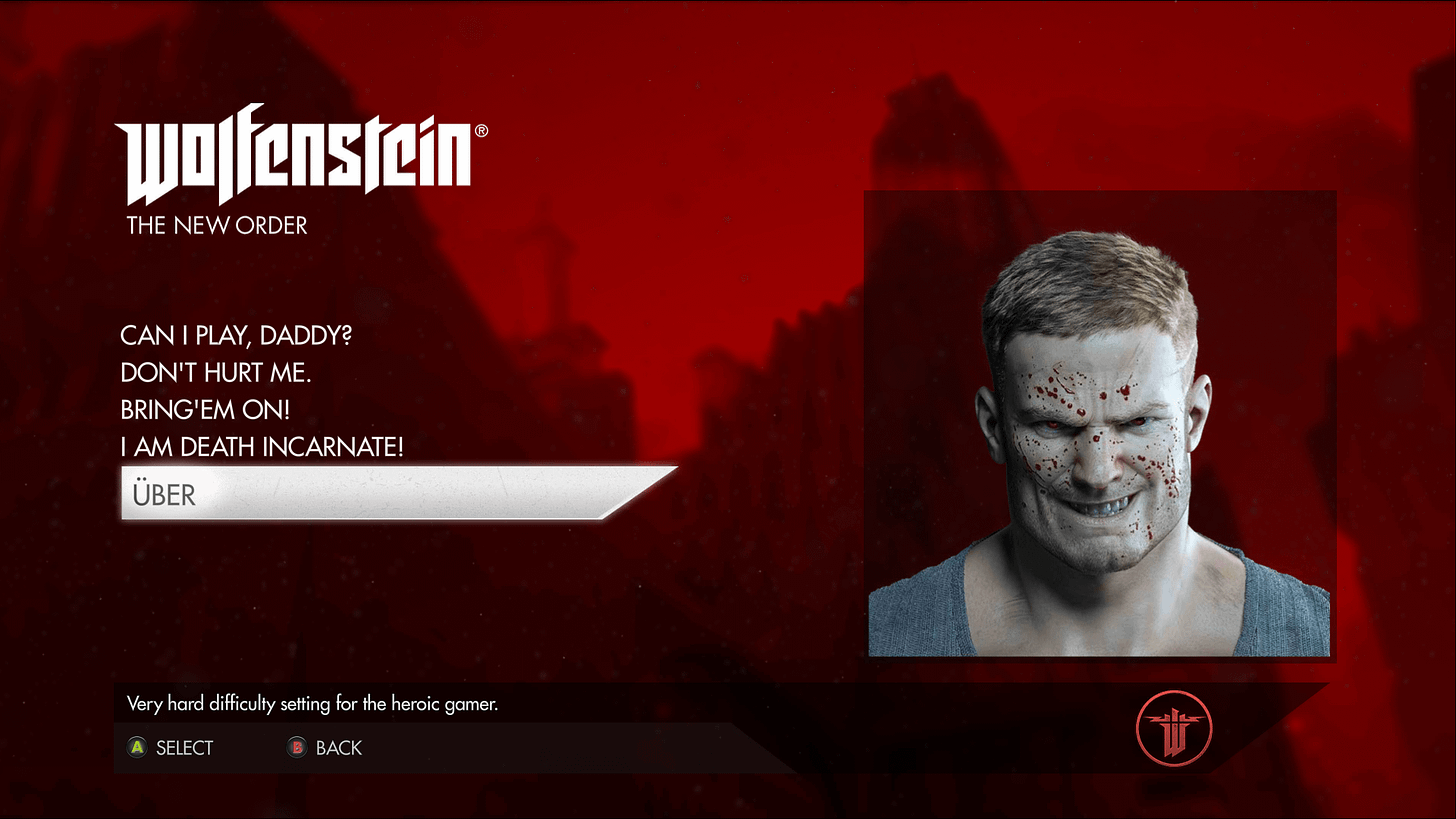

Combine all these factors, and making a game like Veritus—no matter how well you do it—starts to feel like playing on insanity difficulty. It’s the Über setting from Wolfenstein, where the devs try to scare you away from even playing it on the select screen. It’s a no-hit run through Dark Souls. It’s the hard mode of hard modes.

Is it possible for a game that finds itself stuck in “hard mode” to fight its way out? I think so.

In fact, recently I’ve been talking to a developer who has been laboring on the same game for nearly a decade—but is only just now getting real positive attention. So it’s possible. Even games stuck in the depths of the dark valley can evolve into something that markets itself.

But we’ll save that story for next time.

That’s it for this week. I’m gonna go play Kirby and the Forgotten Land with my four-year-old so I have a good excuse to play on the lowest difficulty setting.

See you next Friday.

The best trailers have music to pull you in when they aren't showing direct gameplay and the gameplay has to get to the heart and SOUL of why the game is supposed to be interesting. I see lots of indie game trailers that are built like AAA trailers and they're awful to watch. Just out loud I describe what they've shown to me and often in 15 seconds they've shown that you can run, jump and....there are 4 biomes and some NPCS talk. This is NOT a trailer this is a disaster, SELL GAMES! Just tell me what it is!

The biggest big company offender recently was Princess Peach Showtime, numerous times myself and other commenters couldn't figure out a clear answer to the phrase "what do you do".....trailer after trailer after trailer it was so hard to nail down WHAT you do on the whole.

I was just thinking " I'm seeing alot of similarities in the GTM plans for the games i'm doing case studies on, maybe I should make a post about that" Only to discover you already did it and absolutely killed it.

Damn you Ryan. You insightful entertaining bastard. Seriously tho super fun read!