Games Marketers Are In Crisis Mode

The world's biggest games publishers no longer know how to reliably sell games

I saw something tragic in San Francisco yesterday and was inspired to blast out some disconnected observations on the state of games marketing. So this piece is a little more chaotic and discursive than usual. Shoot me an email reply to let me know what you think.

Next month game devs from around the world will flock to San Francisco for the Game Developers Conference. GDC will be held, as always, in downtown SF’s Moscone Center.

Just a few blocks to the southeast of that venue, there is a near-perfect visual metaphor for the current state of the games industry: a hastily abandoned office that once belonged to Ubisoft. The doors are locked, and the interior lights are off, but outside there are three lamps angled in to illuminate posters for three Ubisoft games.

How long will these lamps remain on? Probably longer than the servers for XDefiant, a game that was killed off barely six months after release.

XDefiant was just one of many recent bungled launches from Ubisoft. Within a single 12-month period, Ubi suffered the same cycle with four separate games: Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora, Skull and Bones, XDefiant, and Star Wars Outlaws. Each of these games launched to mixed reviews from players and critics, sold under expectations, and were swiftly forgotten. But wait, you ask, what went wrong with the last one? What did we learn from it? Didn’t these games cost, like, at least $100 million each to make? Why didn’t they sell? Shouldn’t we do a retro?

And the answer, of course, is that there just isn’t that much to learn. These were all good-but-not-incredible games, and in the games market of the 2020s, making too many “good-but-not-incredible” games can be a death sentence for big-budget studios.

In a previous era, a long-established brand like Ubisoft could simply deploy a big warchest of marketing dollars and drive meaningful sales for games like these. These are not bad games, after all. But that playbook has long stopped working. The only thing in games marketing that really seems to move the needle now is shipping a game that blows players away. Or: spend to support an existing game that has somehow managed to keep players locked in.

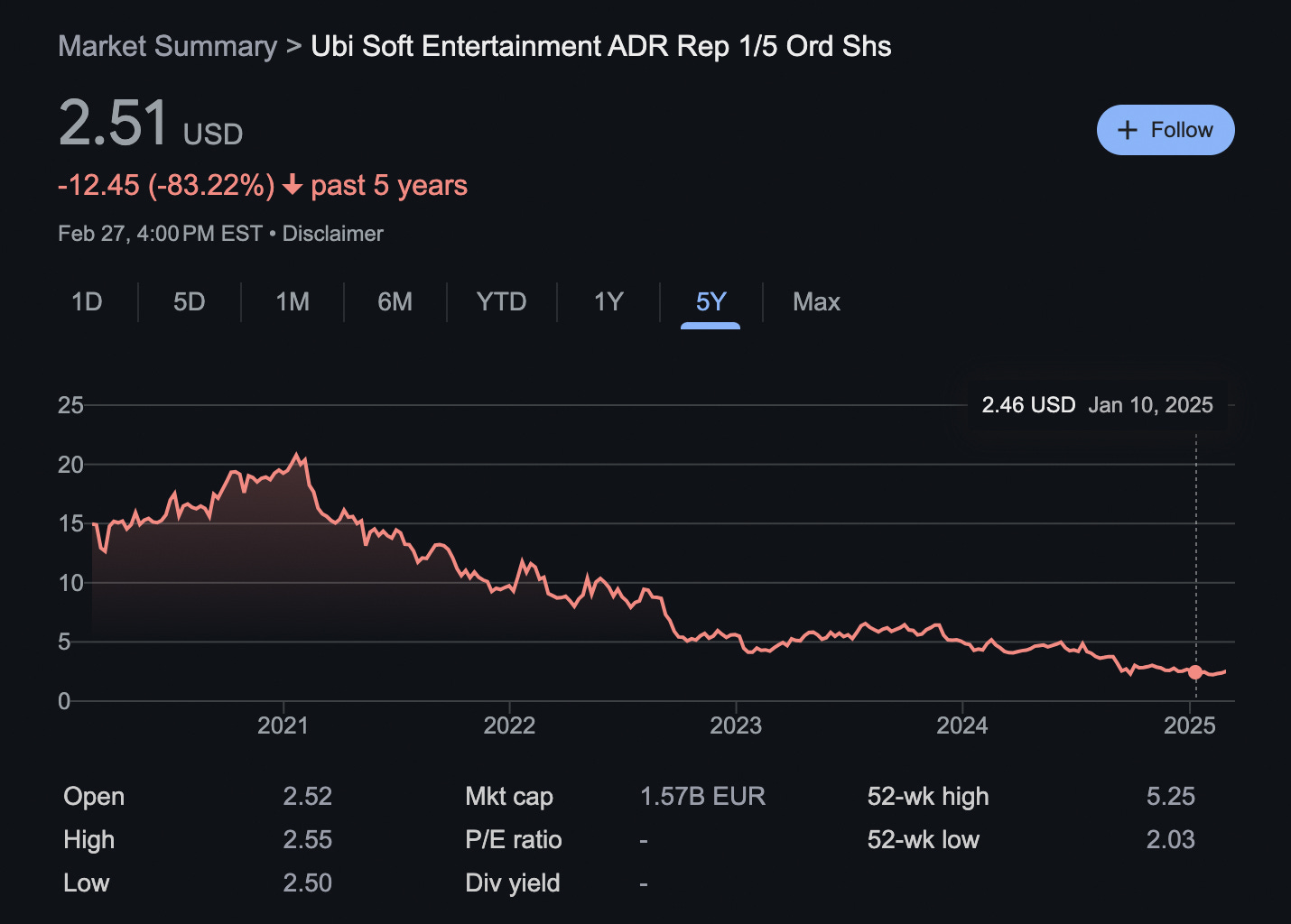

Google says that Ubisoft currently employs 23,000 people around the world, an enormous pool of talent. For these people, the stakes are higher now than ever. This is a company that has been bleeding market cap while growing its headcount for years. Even if next month’s launch of Assassin’s Creed Shadows goes well, there are real questions about the viability of Ubisoft’s business model.

Of course, Ubisoft isn’t the only major games publisher that’s struggling. Warner Bros. is shuttering games studios amid plummeting revenues, and EA expressed disappointment with the performance of Dragon Age: The Veilguard.

As it stands now, you can divide every major games publisher1 into one of two groups: the lucky few riding steady thanks to reliable cash cow franchises, and those desperately searching for a hit.

In the former category, you have publishers like EA (Madden, The Sims, FC, Apex Legends), Activision (Call of Duty, Candy Crush), Riot Games (League of Legends, Valorant), Take-Two Interactive (Grand Theft Auto, NBA 2K), Epic Games (Fortnite), MiHoYo (Genshin Impact), NetEase (Knives Out, Marvel Rivals), and Nexon (Dungeon & Fighter, MapleStory).

In the latter “searching for a hit” category is just about everyone else.

For the lucky publishers with a cash cow franchise, the old-school marketing playbook continues to pay dividends. Big budget, flashy marketing campaigns remind players to buy the new entry and check out the latest update.

But it’s becoming increasingly obvious that this approach doesn’t go far for new or mid-tier IPs. Ubisoft was once in the “franchise kings” category thanks to Assassin’s Creed, Just Dance, Far Cry, Prince of Persia, and a million Tom Clancy spin-off series. But slowly, surely, each of those franchises have faded to mid-tier status—except for Assassin’s Creed. And even AC has shown signs of shakiness in recent years: word on the street is that Assassin’s Creed Mirage sold less well than its predecessor, Assassin’s Creed Valhalla.

The Headwinds Facing Big Budget Publishers

So why is this happening? We could argue over a million factors, but one of the most obvious and least controversial explanations at this point is the decline of paid media and retail. Dollars and relationships simply can’t move things the way they used to:

Paid influencer campaigns now have awful conversion rates as audiences became accustomed to tuning out promotions even from creators they love

Regulations and competition drove down the cost-efficiency of advertising2

Retail relationships became irrelevant (RIP physical media)

What’s worse, the big dog publishers are now up against serious competition from more indie games than ever: There are only so many annual “game hours” that games publishers can tap into, and surprise indie hits like Palworld, Lethal Company, and Stardew Valley actually do cannibalize meaningful amounts of those hours. The rest of the game hours, of course, go to the forever games.

How Indies Are Adapting

Meanwhile, indie game developers are already adapting to the new landscape. In the video below, listen to the way Thronefall creator Jonas Tyroller and HowToMarketAGame.com’s Chris Zukowski talk about go-to-market strategy on Steam. They’re not talking about ads and publishing support. They’re more interested in the discovery algorithms that power Steam.

“Most games, when they launch, 50% of the traffic comes from the Discovery Queue,” Zukowski says in the video linked above. And then the Discovery Queue automatically feeds you more (or less) impressions based on how your game performs each day. But this is almost entirely determined by the quality of the game. “Product is like 90% of of what determines whether your game is going to succeed,” Zukowski says.

Tyroller concludes that there are only four forms of promotion that actually work:

You make a great Steam page with an excellent trailer

You have to make a demo.

You go to an enormous number of content creators (Zukowski recommends hitting up 300–1,000) and say “will you play my game on your stream?” and then send them the link to your demo.

And you apply to festivals on Steam. These lead to wishlists and more organic attention, including from content creators.

If you make a great game and do these things, the Steam algorithm promotes you.

What does it mean if marketing’s impact is limited to the four bullets above?

What Are Big Budget Publishers To Do?

This is the single biggest question facing the games industry as of today. If games publishers who have survived for decades are no longer capable of reliably shipping profitable games, the industry as we know it will collapse. Some part of me thinks that this is inevitable. Aren’t many other industries also fragmenting and deprofessionalizing? Why should games be different?

Certainly, one major part of any real solution to flagging sales in the games industry is to “just make great games.” But that’s tough medicine, and it doesn’t really help us understand what sorts of positive roles marketers can play in the years to come.

I’ve argued here previously for several new approaches: For one, marketers should try to help devs find market signal earlier in the development process for games. Shining a light in the darkness of the market is a hugely powerful way to help avoid disaster. And there are other ways marketing still matters: like by determining smarter positioning and by inventing (or stealing) great tactical ideas.

But what else can be done? Throughout March I’ll be publishing a series of posts examining what sorts of games marketing approaches can actually make a difference. If you’d like to get those in your inbox…

Can you believe I really ended that article with a classic “like and subscribe?”

That’s it for this week. I’ll see you next Friday.

In listing out “major games publishers,” I’m not considering platform holders like Nintendo, Valve, Sony, Microsoft, Roblox, Apple, and Google. Some of these own and publish valuable franchises, but the real money is in the 30% rent they charge to everyone else using their platforms. Nintendo is—as far as I can tell—the only platform holder that makes most of its money from its own franchises.

Unless your “game” is really a virtual casino designed to attract and milk whales

I don't have any solutions, but I wonder how many who enjoy video games are just becoming more and more bored by the same-old, same-old.

The industry is stagnating and there doesn't seem to be any clear explanation as to why. People still want to play video games, but most AAA developers are still pumping out the same type of games they were a decade+ ago.

Indie games can be exciting, or, more often, they can feel cheaply made and highly derivative.

I confess, I'm an older gamer who lived through the 2D era, then the awkward transition to 3D, then 3D games coming-of-age into The Gaming Standard... but the industry has been stuck in the latter for nearly two decades, constantly refining small graphical details while giving us similar-playing games that we experienced in the PS3/360 era.

Time for something new, something we've never seen before.

What that is, I don't know, but my guess is the solution (s) won't be emerging from companies solely interested in their bottom line.

Cheers, Ryan, great article as usual.

"For one, marketers should try to help devs find market signal earlier in the development process for games."

Agree. But as a mobile marketer working on games (from small to very large studios), i often see how disconnected are internal teams, even once the game is launched. Lack of communication & collaboration between product, monetisation & marketing, leading to missed opportunities and growing challenges.

So while i agree marketers should try to help devs early on, i think it also comes to devs having to listen more to marketers when it comes to players feedbacks, market dynamics and competition on the user acquisition side of things.

Looking forward to read your upcoming articles on the subject.