A Theory of the MMO

"The dream of having an alternate holodeck world you step into is too damn big for us to walk away from. People are going to keep trying."

Like many of you reading this I was in San Francisco last week, sprinting back and forth between hotel lobbies for 1-on-1 chats with game devs.

In conversations throughout the week, a few topics kept coming up repeatedly: ongoing layoffs, the dour mood of GDC compared to years past, and the sorry state of the AAA side of the games business, in particular.

But then another theme kept emerging: Everybody I talked to had their own personal thesis for how to build and sell their next hit game. One Scandinavian publisher is creating an elaborate playtesting strategy to greenlight its future titles. Another dev who recently sold a games studio sees opportunity in underserved indie niches. A veteran with 25 years in the industry shared a theory about how Helldivers 2 armed players to spread that game via word of mouth.

These were all people with real skin in the game. They’re putting millions of dollars on the line to test their theses about how to sell hit games. Maybe some are wrong. Or maybe these theses and theories won’t matter much in the end, and the quality of their teams’ execution will determine the results.

But I always root for people that can see a path forward and are willing to bet on it. I hope they’re right.

This brings us to Raph Koster. If there’s any game developer who’s genuinely famous for his theorizing, it’s gotta be Raph. The author of the best-selling book A Theory of Fun for Game Design was also lead designer on Ultima Online, creative director of Star Wars Galaxies, and Chief Creative Officer for Sony Online Entertainment when it launched Everquest II. The man knows MMOs.

But these days, Koster tells me, most people know him for his book—which he says continues to sell every year at basically the same rate it always has. “People mostly know me for that and not for any actual games,” Koster told me in a video call recorded a few weeks ago.

Now Koster has a chance to change that. He’s getting back into the game with a new, ongoing Kickstarter campaign for an MMO called Stars Reach, a game Koster described to me as "massively multiplayer Breath of the Wild."

And Koster has an extremely well developed thesis, really more of a theory: He believes that somewhere along the way, massively multiplayer online games lost their ambition. In a call with Push to Talk earlier this month, Koster explained how the history of the MMO took a winding and particular path that left some grand visions unexplored and unfulfilled.

What follows is the transcript of that conversation, with minor edits for brevity and clarity.

PUSH TO TALK: Can you tell me the story of what happened to MMOs after World of Warcraft? And maybe where they could go from here?

RAPH KOSTER: Okay. So, I think you can't tell the story of what happened after World of Warcraft without telling the story of what came before it. Prior to commercial MMOs, there were text MUDs on online services for pay, and there were all of these free MUDs. These had more design diversity than what we see in the MMO landscape today—lots more. They actually broke into a few different types. There were social worlds, there were hack-and-slash worlds, there were role-play worlds, there were creative worlds, and because different server engines had different strengths and weaknesses, these different genres were associated with the engine. So, MOO meant one that has building capability. And MUSH had better role-playing environments. And DikuMUD was one of the kinds of hack-and-slash ones that, at one point, was like 40% of all of the text MUDs.

When the MMO revolution happened, it happened pretty much around the world simultaneously starting in 1995. We got the Korean MMOs: Dark Ages, Kingdom of the Winds. We got Tibia and DOFUS starting up in France. In the US we got EverQuest and Asheron's Call and Ultima Online, Meridian 59. All starting in 1994, '95. They finished at different times, but they all got going then, right? That's because tech had hit a tipping point. The vast majority of these started out as DikuMUD style games. Which meant you have a tank, nuker, healer, you form a party, kill monsters, move through zones, level up, you know, stun your targets.

Very, very familiar stuff. The vast majority of them were like that. EverQuest's vision statement was actually "DikuMUD with graphics." So much so that they actually ended up having to sign a sworn affidavit that they hadn't used any of the open source DikuMUD code. Because even some of the wording of the messages was the same.

Now, this was also a time period of huge experimentalism in MUDs. Massive, massive experimentalism. And all of us were on one mailing list called MUD-Dev, swapping ideas. All of us, including the developers of all the aforementioned games. Everybody was in touch. It wasn't that large of a community, and there were a whole bunch of ideas happening. Instancing got invented right around this time window. The first MUD to actually have real crafting came along in this time window. Player housing started exploding in text MUDs in this time window. There were just all kinds of these fresh ideas coming together. But it wasn't mainstream, right?

It was this little think tank off in the corner on the mailing list, and when the graphical stuff started happening, most of it was pretty Diku-like, with a massive amount of PvP in there as well. Asheron's Call, had a bit more world storytelling stuff. EverQuest straight up Diku.

And then there was Ultima Online, which was very much not. We consciously had pulled from all of the different MUD traditions and blended them into one project. So you had player housing and crafting and world simulation. We had a different kind of mission statement. And today people don't necessarily recognize that all the crafting in video games comes from Ultima Online.

Like when you go craft your bows and arrows in Tomb Raider, you can trace it back. Decorating a house, this predates The Sims by several years, right? Having a pet, going fishing in a world. Like all of these things. And again, many of them had come to some degree or another from MUDs, but by moving them into graphics, we had to reinvent a whole bunch of it. And it was really kind of the first player-driven economy as well.

So then you get EverQuest, and it does better for a variety of reasons, including because the PvP in UO was overwhelming. Then you get World of Warcraft, which was very consciously about taking EverQuest and making it dramatically slicker. That was Blizzard's M.O. They did that to Dune II to make their RTSs. It's a very common and successful path for games, right? Find something that is a genre or game style that is fresh but needs all the rough edges sanded off.

And then you spend a lot, okay? People complained when UO came out, because we were outspending the text games by millions of dollars because we spent a few million dollars. That was 1997. By the time we did Star Wars Galaxies in 2003 I think it was $12 million.

What do you mean when you say spend? Do you mean just the budget of the game or including the marketing?

Galaxies was $12 million, I think it may have been as much as $20 million when you count the hardware and the marketing and everything, all in. And then World of Warcraft comes along and I think their launch budget was $63 million, maybe $80 million. And they squish everybody. They were able to spend to a degree that nobody else could approach.

And their big innovation was quest streamlining. Quest lines carrying you through the whole game. Nobody else could afford to do that, right? Like, there was just no way. So everybody else got spent into the dirt and it set the template. At this point, that world simulation thing that UO was doing had been market squished. And not necessarily because it lacked appeal, right? The PVP lacked appeal, unquestionably. But the rest of it, today we look around and we see house decorating, having pets. I mean, those are considerably bigger than killing orcs. So the gameplay bits that were in there were on target for a broader audience, right, but got just massively outspent.

And EA did not reinvest into UO. Famously, they tried making sequels like three times and they didn't really reinvest into the original project. So what ended up happening? Well, UO inspired directly—and this is gonna sound like a weird list—both Neopets and RuneScape. When RuneScape came out I was like, holy crap, they made a web-based clone of UO. That's what it is. Because there's no other game on the market in which you wandered away from town, leveled up skills by chopping down trees, right?

And have you seen those concurrent player counts for RuneScape Classic even today? It's astonishing.

Exactly. That's kind of my point. If there had been reinvestment—and Jagex has reinvested, they've always supported that title phenomenally. They've done a really good job of maintaining and updating and all the rest. And there were others, like there were really hardcore ones, like Wurm Online, that was like UO only way more hardcore and with more world modifiability. And there was no market for that, but there was a guy working there named Notch. And then he saw Infiniminer, and if you play the crafting system in UO, and then you play the crafting system in Minecraft, they're identical. It's the same thing.

Survival games are in many ways children of UO as well. So it ended up being really influential, spreading out in a whole bunch of other ways. For EVE Online, their mission statement was "UO in space." And they also invested heavily into it over the years and have maintained it and it's grown hugely. So, yeah, MMOs today, if you look at kind of the mainstream of them, what ended up happening is we had a period where the DikuMUD template dominated thoroughly since EverQuest, since 1999. The vast majority of MMOs made have been level treadmills with content leading up to end games about raiding.

And that game design template hasn't really changed, but there's this host of other traditions that have been kind of left to one side.

Can I articulate my understanding of what you're saying? Because this is fresh to me. It's like: some have thought about the MMO tradition as being defined by certain games, like WoW and EverQuest, but that's actually only looking at one branch or one part of the tree. And actually, the spirit of the MMO has sort of spread out through almost the entire games industry at this point, including things you wouldn't expect, like the survival-crafting branch. So some of the original MMO spirit is living on and thriving, but in this very disparate, spread-out way. Is that basically correct?

Yes, but I'll take it further. Even during the time period that people thought that WoW ruled the world, okay, there's another branch area where this stuff went. Habbo Hotel was bigger than WoW.

Like more players?

Yeah, yeah. Right. There was a period where kids' virtual worlds absolutely dominated and destroyed WoW on a per capita basis. Like, they were huge. I mentioned a couple of those, and they were in some ways more of the social worlds and the MOO worlds. When I described MOO and its ability to build, the most obvious MOO on the landscape for years was Second Life, which is very much in that tradition. We can't overlook it as a type of online world. And today, what is MOO-like? Roblox.

Right, right.

So, I think the common thing that people do is they think "MMORPG" and they think things that are like WoW. And if they're outside the U.S. maybe they think things that are like Lineage. Although, Lineage actually did partake from some UO influence as well. Because Jake1 was paying attention, right? I mean, obviously, they'd actually done Kingdom of the Winds and... Damn it, I literally just said the name of the other one… Dark Ages. They'd actually done those a little bit before UO. They were out the door beforehand. But they were playing during the Alpha and the Beta.

Anyway, it's better to think of the genre as "online worlds" more than just the DikuMUD style MMORPG World of Warcraft. And when you look at it that way, it's like, oh—VRChat and Rec Room today. VRChat is very MOO-like, and Rec Room is more social world-like. And they account for most of the minutes on VR headsets.

So, the interesting thing is, where is the idea of having all those in one world again? Where's the idea of having a simulated alternate reality. People still want that. We know that. Look at the sales of fricking Skyrim. Right? Skyrim is that idea, but single player.

But DikuMUD… it's fundamentally a leveling content consumption model. That root hasn't changed from being: kill monsters to level up and get the next loot. That core loop hasn't really changed since DikuMUD was invented in the early 1990s. And, you know, after a while, it wears on you.

That's true. And I'm not interested in it myself. Like, yeah, I just don't care about that kind of game anymore. It doesn't do anything for me.

It works phenomenally well with free-to-play monetization. And in some ways that can be a bit of a trap because in that model of game you're basically on the little wheel, right? Kill a monster, get a little more powerful, kill a tougher monster, and you just do this over and over. And eventually you reach a top and then they have you doing the same thing but in raid form. And people call it a hamster wheel.

That is entirely dependent on the devs dripping more content right in front of the rolling wheel. You're building new road right in front of it. And if you can sell the road, you can make enormous amounts of money. It gets more and more and more expensive. And it has drawbacks. By the time the wheel's up here, what are you doing for new entrants? You have all this backlog of content. And so what you end up doing—and this has been known since the 90s—you have this phenomenon called mudflation, which is that the value of your database reduces. So when WoW launched, getting to level 60 took months. Today, people do it in 12 to 48 hours.

Wait, say more on this. The value of your database, like the value of the content you already created?

Yes. Yes.

It's compressed down and becomes more quickly digestible? Is that sort of what you mean?

It becomes more quickly digestible because you keep pouring in new capabilities, skills, items, whatever. There's also player knowledge trickle-down—the players just get better. They start speedrunning your content.

So then you start compressing the experience. And now hundreds of millions of dollars of investment no longer provide months of play—they provide days of play. And so you end up in this content treadmill trap. And one challenge with it is that players consume it way faster than you can build it. So there's a phenomenon of people rushing into the new content drop, your game gets a big usage spike, they consume it all in a matter of days, then they go away, and they check back in the next time you do a big content drop.

And that has led to this phenomenon of migrating between games and juggling the expansions and whatever

So then for Stars Reach, it sounds like you're trying to build directly from the foundation of Ultima Online. Is that how you would frame it?

Yes. First, there's the question of: is there an audience out there that is underserved by that dominant DikuMUD model? To which the answer is freaking yes. I mean, obviously, because we have seen those features and gameplay spread out and become the foundations of entire genres. But there isn't a persistent environment available. For example, when ArcheAge came out, it was hailed as the next big thing in MMOs because, wait, you can farm and you can have a house and there's a player government, right? And then they over-monetized it and alienated everybody.

We see that latent demand showing up in all of these other games. We see it driving No Man's Sky, even though No Man's Sky isn't really an MMO. You know, we see it in Animal Crossing. We see it in Eve and RuneScape continuing to thrive because if you are gonna make one of these things your hobby, then hopping off the content treadmill and into something we can play in more ways, particularly ways that—with an aging audience—are less demanding of your time, and require less coordinating with your friends to be able to do anything, right? That stuff matters.

And you can see in the rising audience, because so many kids now come up through MMO-like play. Like, if we think about what are the dominant kids' experiences of literally the last 20 years, okay, I'll just name four titles: RuneScape, Minecraft, Roblox, Club Penguin.

They're all descendants that carry on one part of the tradition for sure. And they are not level treadmills.

Right.

And then those kids grow up and where do they go? Not to the level treadmills. So there is an audience there of younger folk who have not seen an MMO that does all the things that they grow up with. It's just not available in the market.

I see Stars Reach as being the third in the trilogy. If you loved Star Wars Galaxies, it's: let's make a new simulated alternate world. But our internal logline for Stars Reach wasn't, "hey, let's make a modern Star Wars Galaxies." Our internal logline was "massively multiplayer Breath of the Wild." Because Breath of the Wild is basically single-player UO again. The first things you do are pick an apple and craft a sword and then climb a mountain, right? Like that's literally the tutorial of Breath of the Wild.

The dream of having an alternate holodeck world you step into is too damn big for us to walk away from. People are going to keep trying. And to my mind, it's been a lack of will and vision and budget for people to go out and actually take a serious try at it, not a lack of interest and demand.

Song "Jake" Jae-kyung, co-founder of Nexon.

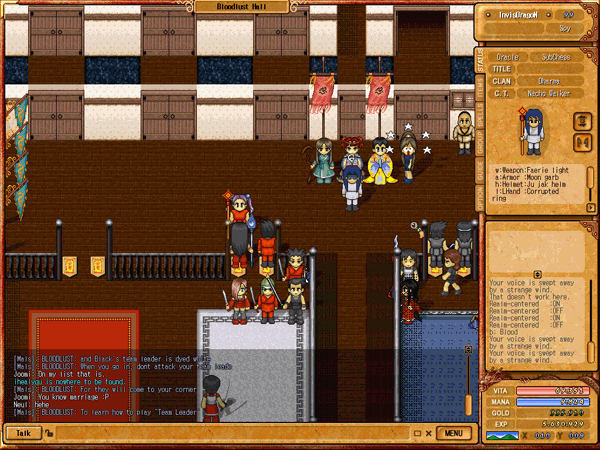

![[IMG] [IMG]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa7fd7faf-7dde-4423-b0da-f753778a4fc4_640x480.png)

Really great read. I ran an emulator for an MMO that shutdown in the mid 2000s for about 10 years. It was a lot of work but maybe the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done because it kept a community alive. My theory on MMOs is that they enable a lot of people to live a life (even if it is digital) that is more aligned to who they want to be. That feels very human to me which is why MMOs will always be around in some shape or form.

The very difficult part of getting them right, though, is balancing sheep vs wolves. You need a lot of players to make the world feel alive. Wolves will play 40-60 hrs a week easily and will vastly outpace the more casual players (sheep). Game Devs need to figure out how to keep both groups engaged because making the game too cookie cutter/easy to keep the sheep happy alienates the wolves. And making time investment too important (for the wolves) will drive away the sheep.

It is hard to get right.

Tibia too is still going after 23 years.