A Divisive Question

Is AI tech getting exponentially better? And if so, what does that mean for the games industry?

A lot of writing about games focuses on their value as commercial products: on the money they can generate. Or on the hours of attention they can absorb.

Others see the primary value of games as escapism. Games are really—and I’ve heard even people who sincerely love games say this—a tool for temporarily leaving the woes of the world behind.

My POV is that games can be more than that. Games are a nascent art form. They’re a vehicle for self-expression. Games are a creative medium worth exploring for decades, or even a lifetime. They are an arena for greatness. And sure, they can also be hugely profitable products in an industry with fascinating marketing challenges. My ambition for Push to Talk is to write honestly about the industry, and as a marketer, I often focus on the commercial side of the biz. But I try to balance the business talk with the more inspiring stuff. For subscribers to this newsletter, I hope I’ve earned your trust with this approach.

Because I’m probably about to cash in some of that goodwill by writing about one of the most divisive questions facing the games industry.

AI is too big of a topic to cover comprehensively in one post. It’s impacting politics, economics, energy, entertainment—and it feels unavoidable. AI pop-ups are in our documents, our emails, our search bars, our notifications, and our “for you” feeds. That lo-fi hip-hop song YouTube is recommending you was probably AI-generated. More and more of the images we see every day are AI-generated. Even the tariffs were probably AI-generated. This stuff is everywhere.

And it’s divisive. Much online conversation about AI tech has taken on the tenor of other culture war clashes, with uncrossable battle lines drawn between the cult of the coming machine gods and the “AI bad” #resistance.

I have friends on both sides of the aisle. A doctor I’ve known since childhood is determined to use emerging models to improve early lung cancer detection rates. Another lifelong friend, a programmer, was raving to me this week about what he’s been able to pull off using AI coding models. Pretty much everyone I know in venture capital genuinely believes we’re in the beginning of a revolution that will make the world wealthier, healthier, and possibly even more free.

Many of the artists and writers I know, on the other hand, probably started seeing red while reading that last sentence. They see AI models—particularly the generative variety—as a fundamentally unethical technology built on IP theft and wasteful energy usage1 which, ultimately, will destroy the careers of artists and submerge entire creative industries in an ocean of slop.

Even if the world envisioned by the optimists comes true, it’s possible the critics are also right. A world with less work could also turn out to be a world where, as Hayao Miyazaki said in a resurfaced documentary clip that made the rounds recently, “humans are losing faith in ourselves.”

I’m not going to play the fence-sitter on this issue. By nature I lean toward the more optimistic viewpoint. Or maybe a better word to describe my view would be melioristic. That is: I think sincere human effort will probably enable us to adapt to whatever is coming. We are almost certainly going to see new laws—or, failing that, court decisions—about attribution and transparency for GenAI specifically. It’s sort of a gut feeling, but I think there has got to be a way to train capable models while regulating their output to respect copyright laws (and more broadly, while respecting creators). The right path isn’t clear to me, though, and I don’t feel qualified or motivated to convert anyone to a more optimistic viewpoint. That’s not why I’m writing this.

Instead, I want to share something I’ve noticed after having a lot of open and honest conversations about AI with both optimists and pessimists. And that is that you can predict a lot about how people view AI based on their answer to the following question:

My guess is that for some of you the answer feels completely obvious, and for others the question barely makes sense. What would it even mean for AI to “improve,” if you see its increasing power as a fundamentally negative force? I sort of like this ambiguity—but let me explain what I mean:

Exponential tech through history

First: It is undeniably the case that exponentially-improving technologies exist.

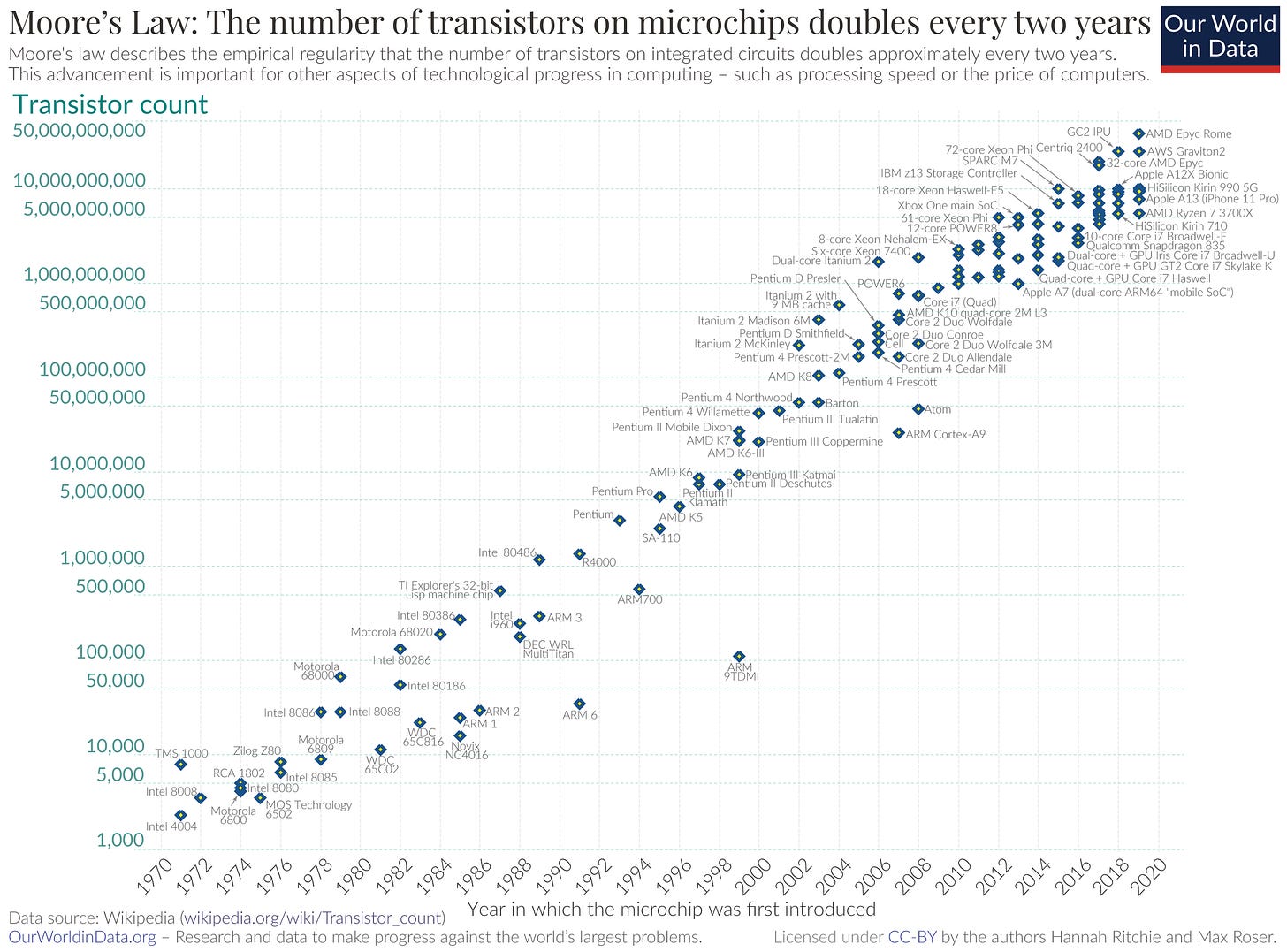

The most famous example of this is computer microchips, which roughly doubled in size (while dropping in price) every ~2 years for half a century:

Every year, computers got cheaper and better in measurable ways. The chart above is in part a history of the video game industry. The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) used a MOS Technology 6502 chip, for instance (from 1975-ish). The Nintendo 64 ran on a custom MIPs R4300 (see the first R4000 at around 1991 on the chart).

In part, the above chart shows one view of a decades-long competition between Intel, IBM, Arm Holdings, AMD, and others. This competition should matter to you if you care about games—because the games industry itself only exists because of the underlying trend shown here.2

Moore’s Law is just the most famous example of exponentially improving tech, along with obvious examples like internet speeds and data storage, which also have had exponential price-efficiency gains.

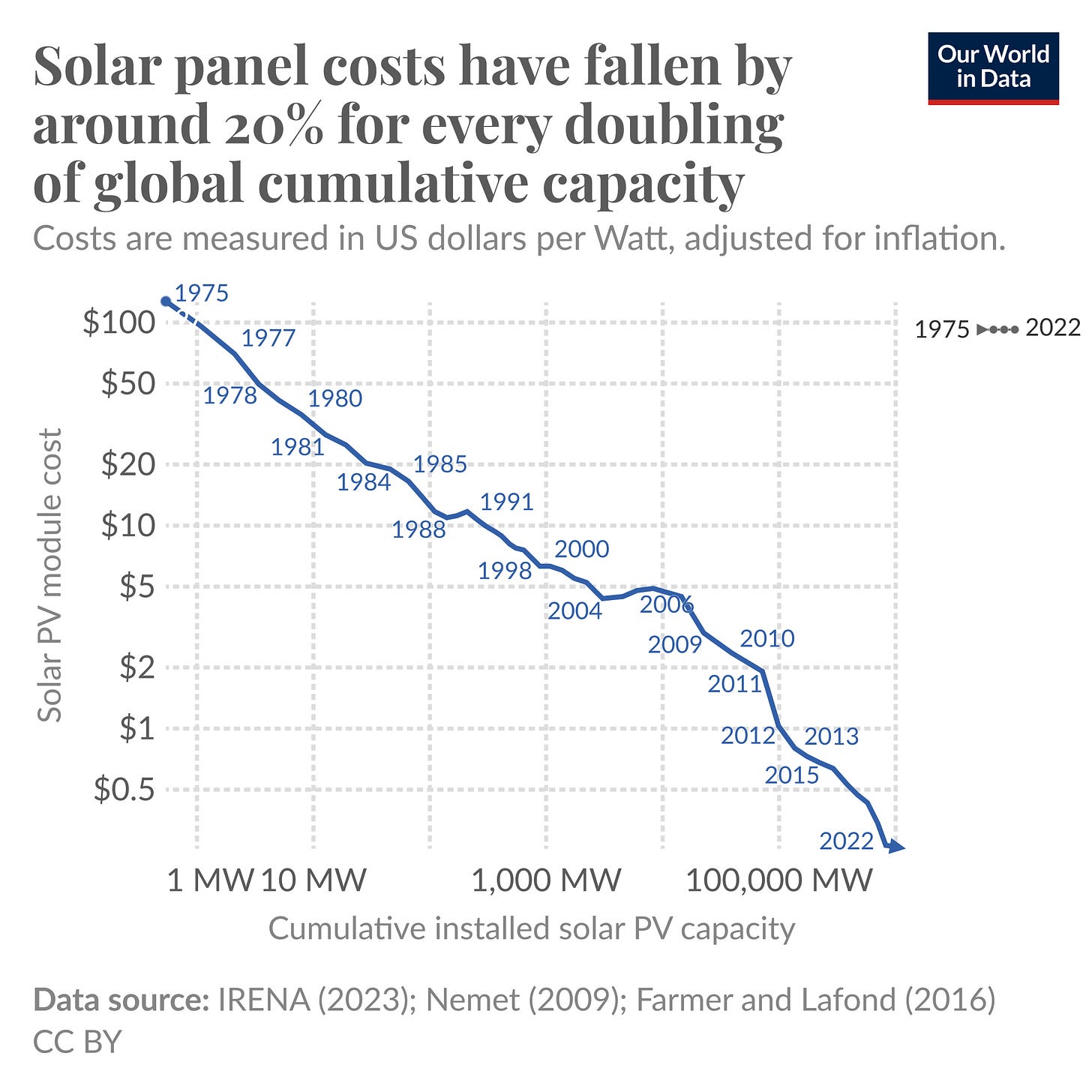

But a lot of people are surprised to learn that something similar has been happening with solar technology for decades:

Basically, every time we double the number of solar panels produced, we figure out ways to make more solar panels for about 20% cheaper.

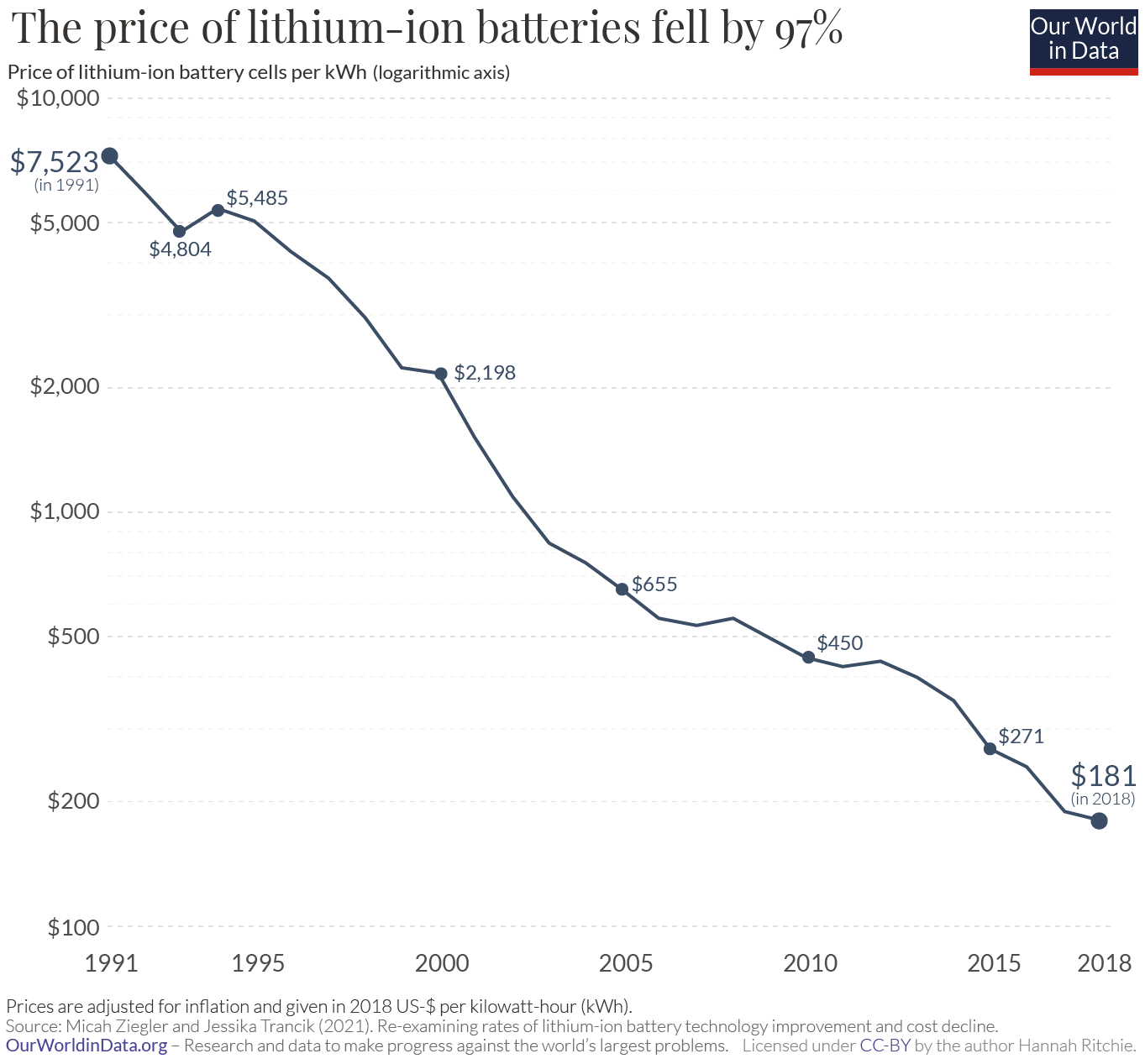

And look at what’s happening with lithium-ion battery pack prices:

That chart cuts off at 2018, but the trend has continued. There was even a huge 20% price drop between 2023 and 2024 alone. If you care about renewable energy, these are two of the most beautiful charts imaginable.

This phenomenon—of prices falling and tech getting more efficient as production increases—is called Wright’s Law. There are a few possible explanations for how it works:

Learning curves - Basically, humans learn new and more efficient ways of making things the more experience we get making them.

Economies of scale - Making things in bigger batches tends to reduce the per-unit cost

Infrastructure development - Supply chains and institutions (including legal regimes) adapt to better accommodate technologies with larger production volume

As far as I can tell, all of these things are happening for artificial intelligence—AI models like the ones produced by OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google will almost certainly get cheaper and more efficient over time. And if history is any guide, the core underlying technologies should become more powerful as well. But what does that actually mean? It’s not obvious that AI models will get exponentially smarter even if their price-efficiency improves.

The problem is that it’s not clear how we should measure AI progress. The models are definitely getting bigger, as measured by the amount of data they ingest, the number of parameters in the models, and the amount of compute that powers them. But how should we measure their usefulness?

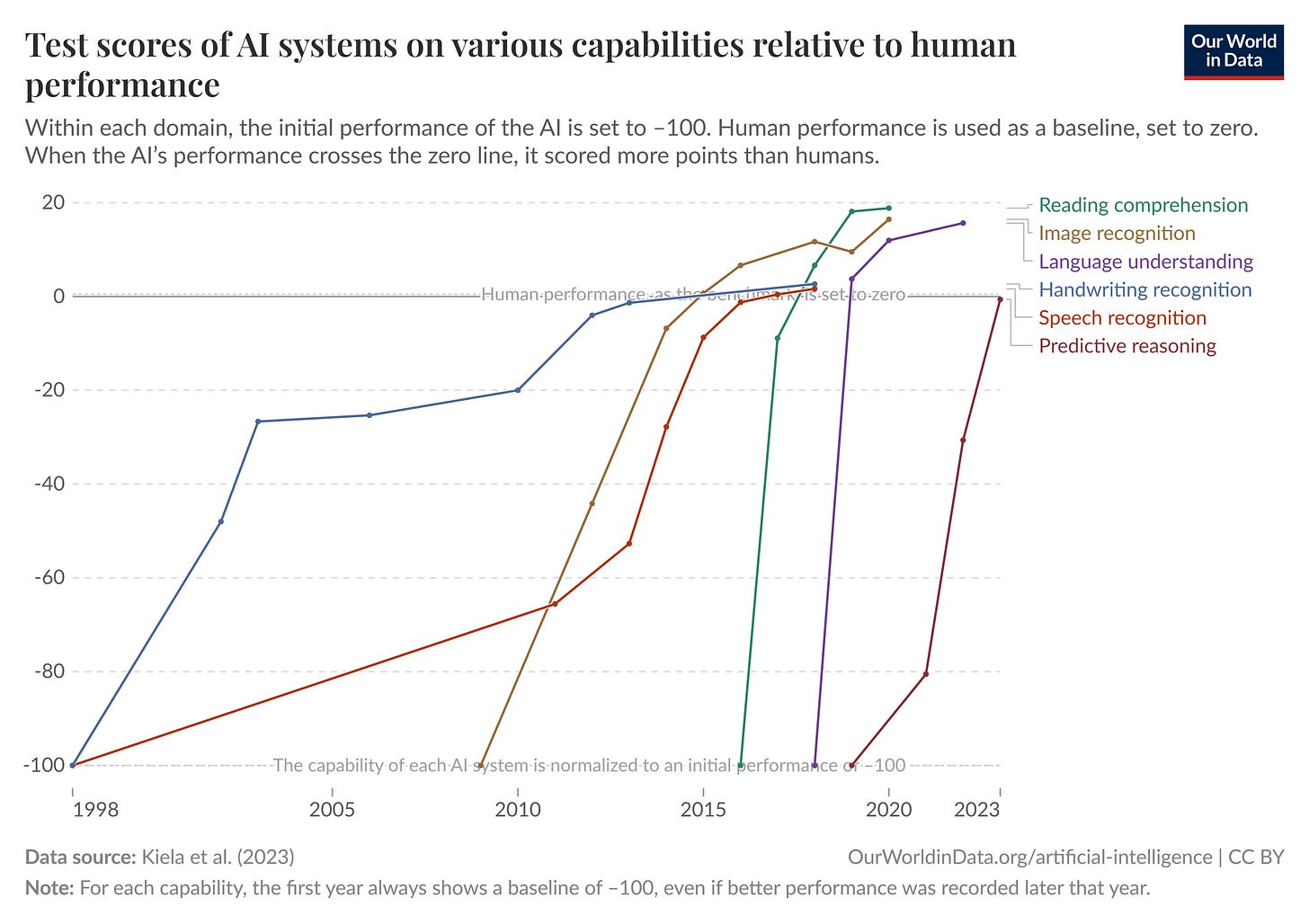

Attempts along these lines have been made, mostly by devising increasingly intricate tests for specific skills like reading comprehension and image recognition:

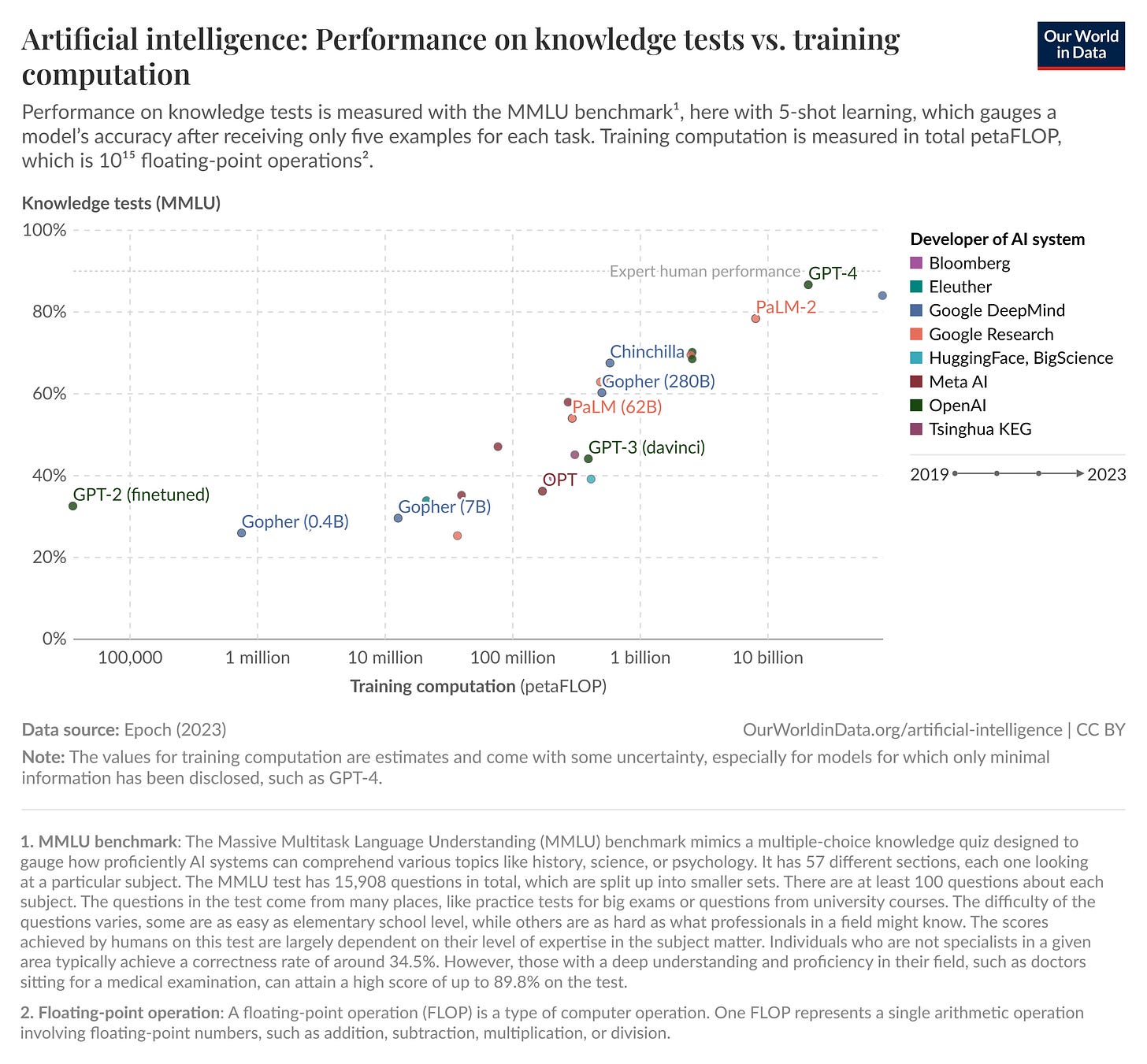

There’s also an entire emerging cottage industry of “knowledge tests” which attempt to establish consistent benchmarks for models to compete against:

One criticism of these tests is that by focusing on the specific kinds of questions that LLMs can be trained to answer, they miss too much of the broader picture of intelligence and usefulness.

This is one reason why—contra claims that extremely powerful AI systems are coming soon—there are plenty of voices arguing that scaling up AI isn’t leading to AIs getting smarter or more useful. Ed Zitron has argued this explicitly, and even some of the Bay Area Rationalists are saying things like “Recent AI model progress feels mostly like bullshit.”

But, coming from the opposite direction, there’s another criticism that I’d aim at these tests: They don’t capture the emergent capabilities of customized AI models. For example: Google DeepMind created a tool powered by the same tech that powers generative video models to make the world’s most powerful weather prediction model.

From that linked piece (which I wrote for the a16z speedrun newsletter):

It’s not obvious that GenAI tech could be useful for predicting the weather. But Matthew Willson, a Staff Research Engineer at Google DeepMind and one of the co-authors of the DeepMind paper in Nature, tells speedrun that there are surprising similarities between video generation and weather prediction.

“In a crude analogy, we can think of a weather reanalysis dataset like ERA5 as a gigantic, many-channel, 4-dimensional video of the atmosphere,” Wilson says. “Thus we were able to adapt some diffusion methods used for conditional video generation, to generating weather forecasts.”

This strikes me as important. Very few people would have predicted that improving GenAI video models would lead to better weather prediction tech. That’s not something that could be captured on any sort of benchmark.

Other examples of surprising, emergent applications of AI tech are popping up all the time. Vision models are helping blind people to “see” again, while audio models are making movie dialogue easier to hear. There’s a whole “search” branch of the AI tech tree, separate from the generative branch, that seems to be getting really good at searching large possibility spaces and discovering things like new materials and potentially life-saving drugs. Of course, by now it should be obvious that the “AI” label is being used to bucket together several distinct technological primitives, arguably separate technologies that could evolve in different directions and at varying speeds.

Why It Matters for Games

Let me bring this all back to the question asked at the top of this article. How should the games industry think about this? So far, we’re still in the “tech demo” era of AI in games. Devs are just starting to use tools to speed up development of assets. More and more code is being written by bots. And companies are spitting out weird, surreal interactive genAI video model demos that cause John Carmack to get into fights with strangers on the internet.

If you don’t believe that AI tech is likely to improve exponentially from this point in the coming years, it’s easy to write all this off as an annoyance. Maybe some games will get minor innovations like better NPC behavior and AI-powered companions, and artists will continue clashing with management over the usage of generative assets—business as usual, in other words. It’s possible it actually goes this way! This is more or less how the last decade went for web3 and gaming, after all.

But if there does begin to be mounting evidence that we haven’t found the ceiling on frontier model AI progress, and the whole field has the qualities of an exponentially improving technology, then a very different approach is called for. If AI tech improvement means we’ll get not just better LLMs but entire new emergent applications and computing paradigms, then some of the squabbles we’re having today would start to look like small peanuts compared to the challenges and opportunities looming around the corner.

It would again raise the question: what are games? Are they an artform? Another commodity? Or have they always been a Trojan Horse for something much bigger?

We’re gonna find out soon enough.

For some really interesting data about AI’s impact on energy usage, check out this incredible piece from Hannah Ritchie’s Substack. Ritchie is a Senior Researcher at the University of Oxford and also the deputy editor at Our World in Data, which is the source for all of the charts I used today.

The other story not shown on this chart, but hinted at, is the direct historical connection between games and AI. The company powering a huge percentage of AI chip R&D today, NVIDIA, was effectively a games industry company. Speaking about why he founded the company, Jensen Huang once told Fortune this: “We also observed that video games were simultaneously one of the most computationally challenging problems and would have incredibly high sales volume. Those two conditions don’t happen very often. Video games was our killer app—a flywheel to reach large markets funding huge R&D to solve massive computational problems.”

I'm a skeptic on the exponential improvement of the models themselves. I think it's more likely to be logarithmic. Google got 80% of the way to making a self driving car in 2018. 7 years later it's only 90% of the way there.

But even if the tech doesn't get better, there's already space for a boom in gaming just by increasing our understanding of how to use what we have.

People who code have only just begun to realise how revolutionary it is to be able to talk to computers in English. We haven't even began to touch those implications in game design.

For example, with existing tech, I think we already can create an entirely new subgenre of RTS where you control armies by sending orders from HQ instead of explicitly clicking them. "Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, follow the enemy, and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns." Mistakes will only make that funnier and more 'real'.

Imagine Mass Effect where you can tell Garrus to flank the enemy without pausing combat.

Imagine the meta city builders where you tell the computer to build you a particular type of city or structure, and it will generate a template for you to fit the tone you specify

People judge AI by the ways they see it affecting their lives.

I can't look at photos anymore without squinting at it to determine *am I looking at something real?* I search for real life photos to use as reference to study structure and lighting, and the AI images cluttering the results are more than useless for my needs. I look at restaurant menus and see pictures of food that doesn't exist.

I see news articles AI generated from reddit comment threads. I see Studio Ghibli's work used to promote the Israeli military. I see fake social media profiles astroturfing for scummy politicians. Job postings are fake and job applicants are fake.

AI computation tools for weather and medical diagnostics are cool, but AI a scourge in marketing and creative fields.